Social Workers Can Lead the Way in Addressing Health Inequities

COVID-19 has exposed massive health and health care disparities for people of color, brought about by systemic racism and social determinants that impact health and well-being. Social workers are expert in addressing these issues, and should be a central part of the solution.

If ever there was doubt, the COVID-19 pandemic has confirmed the need to address health inequities as we care for our patients and their loved ones. Since the start of the pandemic, we have witnessed an increased demand for palliative care specialists to overcome the health care system’s deficiencies in skilled communication and human caring. These gaps have been especially problematic as the pandemic has disproportionately affected communities of color, with Black, Hispanic, Latino, and American Indian/Alaska Natives (AI/AN) persons having higher COVID-19 morbidity and mortality than white persons, and Asian Americans experiencing increasing COVID-19-inspired discrimination and violence. Furthermore, as we have moved into later stages of the pandemic, disparities in vaccine administration are at least partially explained by continued inequities in the rollout, as well as the medical system’s failures to earn (or deserve) trust.

"Social workers on palliative care teams are especially prepared to provide a social justice lens through which to consider the impacts of COVID-19.'

Social workers on palliative care teams are especially prepared to provide a social justice lens through which to consider the impacts of COVID-19. This blog describes how attention to social determinants of health underpins the social work profession, and how palliative care teams can better leverage social worker expertise to address health and health care inequities in their patient population.

Social Determinants of Health and the Social Work Profession

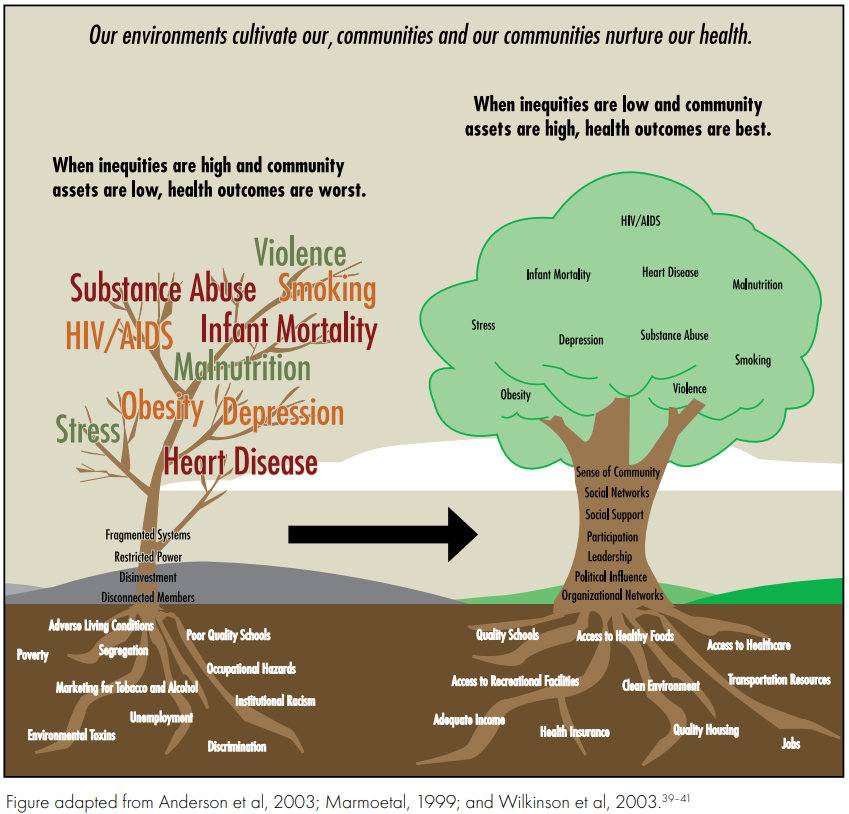

Dame Cicely Saunders (who was at once a social worker, nurse, and physician), often wrote about the concept of ‘total pain.’ Not only pain from physical symptoms and emotional distress, but also crises of faith, identity, and meaning. Included in the concept of total pain is the threat to social belonging intrinsic to any serious illness. This is heightened among populations historically marginalized and deprived though racism, “punishing the poor,’ and other characteristics – often punished by the dominant culture of sexism, ageism, classism, able-ism, xenophobia, and homophobia (to name only some). Structural barriers to affordable housing, equal education, transportation, food and nutrition (i.e., social determinants of health [SDOH]) have obvious and direct adverse effects on health, but their cumulative effect on feeling seen and respected, on educational attainment, employment, access to and quality of health care, and health status magnify these health inequities.

The complexities in care and quality of life for people already living with serious illness are compounded by social inequities, such as paying for expensive medications, and reduced access to nutritious foods, transportation, translation services, and safe housing. These barriers are far more common for Black, Hispanic, Latino, AI/AN, and other persons of color who are living with serious illness due to generations of systemic racism; and, as a result, these populations experience significantly worse health outcomes than white Americans. (In recognition that these outcomes represent a profound failure in our society, more precise language may be on the horizon that helps us to close the public health gaps through moral determinants of health.) And this is particularly relevant during the pandemic, which has highlighted a direct and devastating connection between inequities in SDOH and COVID-19-related outcomes.

"At its core, social work has always been defined by its advocacy for the most vulnerable populations."

At its core, social work has always been defined by its advocacy for the most vulnerable populations. The profession is rooted in a set of core values that include, but are not limited to: 1. social justice; 2. dignity and worth of the person; 3. integrity; and 4. competence. The National Association of Social Work’s (NASW) Code of Ethics compels us to consider our ethical duty and responsibility in addressing barriers to equitable care for the most vulnerable persons in need of care for a serious illness. This includes the expectation that social workers have the knowledge, skills, and abilities to:

- Identify a patient and family's unique psychosocial needs, distress, or complicated grief

- Assess and enhance patient/family strengths and coping skills

- Identify psychosocial interventions to be offered as part of the evolving comprehensive plan of care, developed in accordance with the patient's/family's wishes and the interdisciplinary team

- Provide intervention for specific symptom relief and to reduce risk for distress

- Assess and managing psychosocial aspects of pain

- Evaluate the efficacy of treatment interventions

As a practical matter, social workers are educated and trained to apply the “person-in-environment” (PIE) framework, which links a person’s behavior to their past- and present environment. It is considered a holistic framework because it encompasses several approaches that look at individual behavior, psychological state, and family system (micro-level); local environment and relationships (mezzo-level); and systemic factors (macro-level). This attention to mezzo- and macro-level circumstances necessitates that social workers have a comprehensive understanding of the SDOH that are so closely linked to health – especially so for already vulnerable populations.

"[...] Social workers have a comprehensive understanding of the SDOH that are so closely linked to health – especially so for already vulnerable populations."

Throughout the pandemic, social workers have been at the forefront of embracing new approaches to/technologies for care delivery and bridging gaps in connection; providing psychosocial support and trauma-informed care; maximizing referrals to community supports, including securing health insurance coverage for eligible clients; informing the delivery of culturally competent care; navigating complex ethical challenges; and providing emotional support to our teammates during this difficult time. At the macro level, we advocate for national policies that address the disparities and inequities that have harmed Black, Hispanic, Latino, AI/AN, Asian American and Pacific Islanders, and so many others for so long. And we have continued to hold our own profession accountable – as of publication, social work boards in at least nine states include cultural competence (or something similar) as a topic-specific continuing education requirement for maintenance of licensure.

Practical Steps You Can Take to Improve Health Equity

According to the National Palliative Care Registry, 68% of palliative care programs reported having a social worker on their team in 2018. As palliative care leaders, there are actionable and practical steps we can take to empower our social work colleagues, and to help support greater healthy equity in palliative care.

1. Ask the social worker on your team about the greatest burdens and unmet needs in the population you serve.

Catalyze the effort by encouraging social workers to link to external sources of support for patients. You can prioritize their efforts to collaborate with community partners that serve vulnerable populations and reduce health inequities among people living with serious illness. Some examples include:

- Partnering with a local or national disease-specific organizations (e.g. Alzheimer’s Association) to learn more about supporting the needs of patients and their caregivers.

- Forming collaborative relationships with organizations that identify and support specific races, cultures, religions, and/or ethnicities, to learn about new resources and unmet needs. This allows for bi-directional knowledge-sharing and reduces misinformation.

- Working with local governmental agencies to advocate for the needs of patients with serious illness. This would provide your organization with a platform to identify key priorities, align on shared goals, and participate in innovative research or grant proposals for populations facing health disparities and inequities.

2. Lead with purpose and develop a vision and mission encompassing reducing health inequity. This requires development of and adherence to an equity strategic plan.

At Ascension, we formed a system-wide framework called ABIDE (Appreciation, Belongingness, Inclusivity, Diversity, and Equity) to listen, pray, learn, and act to address racism and systemic injustice. One of the goals of the framework is to ensure that all individuals are treated justly and respectfully with equal access to opportunities and resources, using validated screening tools. We are also launching a new SDOH screening tool and online resource referral platform to make a difference for all community members. Examples based on the World Health Organization definition and model can be found here and here.

3. Listen to patients and families about what matters most to them, and about their greatest worries.

In 2017, 52.8% of adults aged 18 years and over reported that their health care providers always involved them in decisions about their health care. These numbers are much worse among people of color and other minority groups. Promote culturally-competent communication and other standards of practice that enable specialists to build trust and engage the patient and/or proxy when addressing complex symptom management, psychosocial, spiritual goals of care.

Wrapping Up

The social worker on your team may be one of your strongest assets for reducing health inequities in palliative care delivery and beyond. Lean into them for their guidance and expertise. Learn more about palliative social work as a specialized area of practice by speaking with your social work team member and/or accessing the following online resources:

- CAPC's social work resources

- Social Work Hospice & Palliative Care Network

- Advanced Hospice & Palliative Care Social Work Certification program

- National Association of Social Workers

And if you have a case study on how you are addressing inequities in care, consider entering your project in CAPC’s Tipping Point Challenge.