Using Palliative Care to Support Equitable Care in the Midst of COVID-19

COVID-19 has thrust a spotlight on inequities in the U.S. health care system for populations at risk for disparities. African Americans, Hispanics, Latinos, and American Indian and Alaska Natives entered this period in our history already bearing the consequences of structural racism in the forms of increased morbidity and mortality. Poor societal preparation for the pandemic and inconsistent government responses have only exacerbated these outcomes.

Addressing the consequences of health and health care inequities, as well as their origins and the systems that allowed them to flourish, will require the participation of every individual and institution in this country. In the meantime, palliative care teams have an opportunity to be among the leaders in restoring trust and preserving the dignity of care for those disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. CAPC is committed to supporting teams in this effort by providing resources to promote health equity. This blog highlights some of the challenges confronting populations at risk for disparities during the pandemic, with a focus on the African American experience; further describes palliative care’s ability and obligation to promote equitable care; and highlights relevant CAPC resources to support this work. Future posts will address disparities in access to palliative care among other groups in our society.

Palliative care teams have an opportunity to be among the leaders in restoring trust and preserving the dignity of care for those disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

COVID-19 and Health/Health Care Inequities

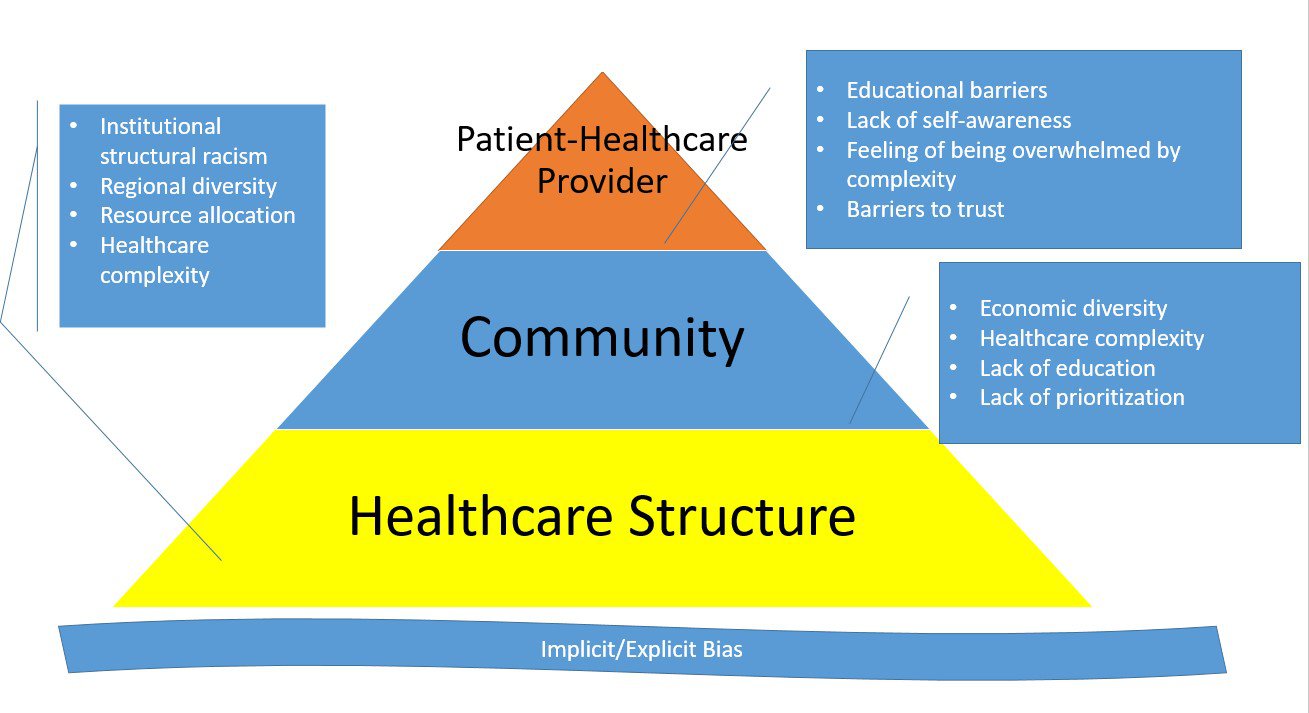

Racially-driven inequities in health (i.e., higher burden of illness) and health care (i.e., differences in access to and quality of health care services) existed long before COVID-19 emerged. Historically, African Americans have had higher rates of morbidity and mortality than White/Caucasian people. The reasons for these inequities are generally outside the scope of this blog, but it is worth reinforcing that they exist at the individual, organizational, community, and societal levels.

The pandemic has exacerbated these inequities, with emerging data showing a disproportionately negative impact on traditionally underserved communities. African Americans in particular are contracting COVID-19, being hospitalized, and suffering significantly higher morbidity and mortality rates than White people. Specifically, African Americans comprise approximately 13 percent of the U.S. population, and yet account for 27 percent of coronavirus cases (as of 5/22/20), and 23 percent of deaths. A closer look at data broken out by location reveal even greater disparities; for instance, in New York City, Black/African Americans have died from COVID-19 at a rate of 201.6 deaths per 100,000 people—nearly double the death rate for White New Yorkers (101.3 deaths/hundred thousand). Additional data show that Hispanics, Latinos, and American Indian and Alaska Natives also have outsized infection and death rates. Future CAPC blogs will explore some of the unique experiences and challenges in these communities.

Leading Up to the COVID-19 Palliative Care Encounter

As African Americans who have tested positive for COVID-19 seek out health care, many may experience a constellation of emotions related not only to a new and frightening illness, but to the unjust circumstances that put them at higher risk of infection (crowded housing and neighborhoods; essential worker roles increasing risk of exposure; poverty; and the comorbid chronic illnesses (hypertension, diabetes) that accompany these social determinants of ill health), and fears and expectations that they will receive poor care because of their race. Here are some examples of COVID-19-related inequities these patients encounter in the days and weeks leading up to an emergency department visit or hospitalization.

- Increased Exposure to COVID-19. Many of the social and environmental factors that placed African Americans at higher risk for other illnesses also increased the risk of contracting COVID-19. For instance, living in densely populated urban areas and/or hypersegregated locations (including nursing homes), or being homeless/housing insecure or incarcerated have all been associated with higher infection rates. The legacy of housing discrimination has created additional risk factors, such as living in food deserts that require residents to travel further and increase their exposure just to eat. Meanwhile, it has quickly become apparent that social distancing to curtail the spread of COVID-19 is a strategy of privilege. Racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to work at low-wage jobs that do not offer benefits such as sick leave (paid or unpaid), or pay enough for workers to absorb any income loss. Many of these jobs do not allow for remote work, particularly those performing essential services such as first responders, public transportation workers, trash collectors, grocery store clerks, health care workers, meat packers, etc. Furthermore, many employers in these industries have not taken sufficient steps to protect employees.

- Inadequate Access to Testing. Even as people of color face greater risk of exposure to COVID-19, they also experience greater barriers to testing. Challenges include not knowing where to find testing; needing a referral from a usual care provider; bias in screening questions; testing being concentrated outside of areas in highest need; and concerns about testing affordability. Making this worse are clear indicators that certain people (e.g., government officials, sports teams, celebrities) had easy and frequent access to testing. Even as testing becomes more widely available, concerns about scarcity, reliability, and cost still present barriers.

- Concerns About Seeking Care. Despite the high incidence of COVID-19 in African Americans, many delay care due to justifiable concerns about the quality and the cost of the treatment they will receive. Just as the infamous Tuskegee Study and other unethical and traumatic interactions with the health care system solidified a foundation of mistrust, more recent events (up to and including COVID-19) have reinforced this in younger generations. More direct causes for mistrust include providers failing to navigate linguistic or cultural barriers, implicit or explicit biases leading to mistreatment (e.g., lack of pain or symptom management), and outright racism. Furthermore, the first COVID-19 wave has largely been characterized by an uncoordinated response at multiple levels and sectors, leading to resource scarcity—most often associated with ventilators, but more recently with medications. As institutions began reviewing and updating resource allocation strategies (so-called crisis standards of care) at the onset of the crisis, the inclusion of underlying health conditions as a criterion in some drew criticism due to the double victimization—since increased comorbidities are correlated with societal inequities. Taken together, these experiences have given people of color ample reason to believe that they will not be triaged, diagnosed, or cared for in the same way that White counterparts would be. Meanwhile, cost also continues to be a factor, since there are still many unknowns about COVID-19 treatment, and people of color often have less generous insurance benefits and/or supplemental coverage.

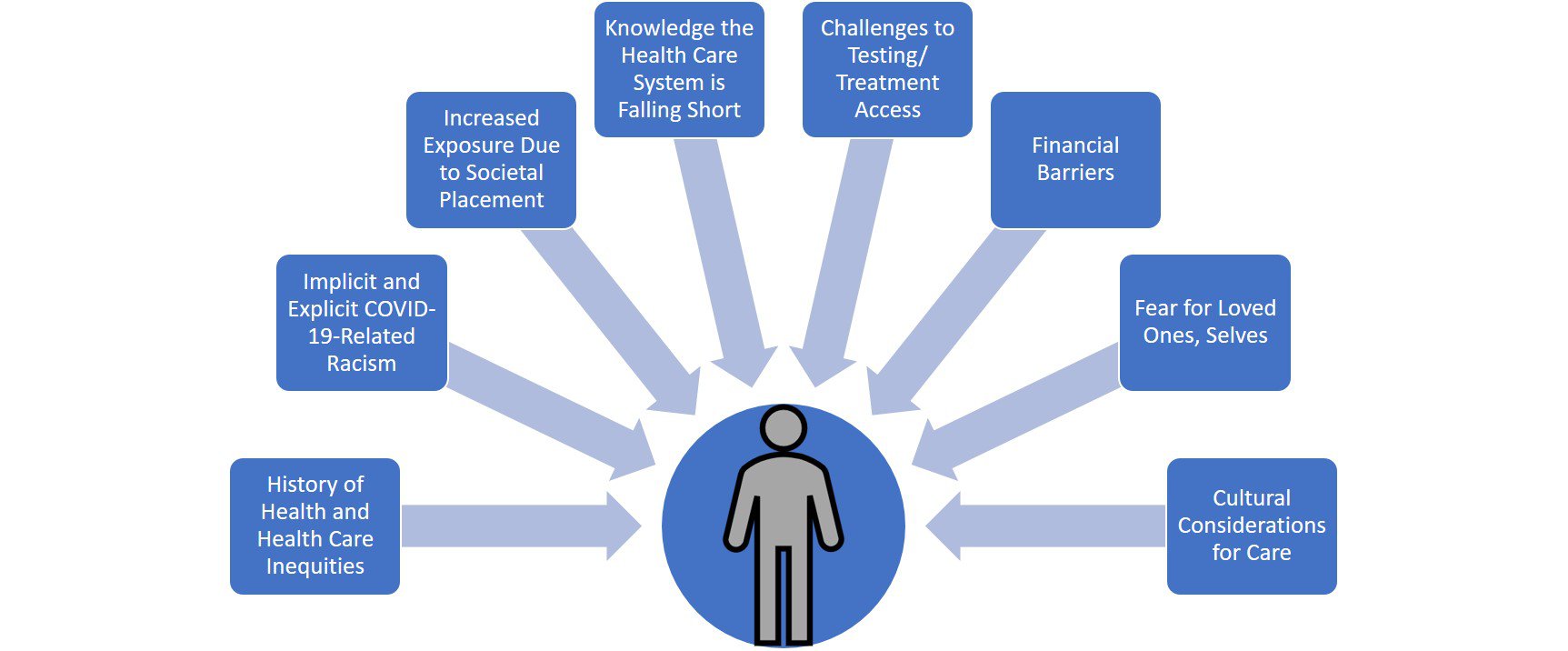

Again, these are only some examples of the challenges and harm many African American patients (and to some extent, patients of other races/ethnicities) have encountered during the pandemic. The following image highlights additional factors that may inform COVID+ patients’ experience of care as they make their way into the health system.

The collective impact of these experiences can lead many patients of color to question if their lives are valued in the U.S. health care system. Questions can include whether their suffering/symptoms will be believed and whether they will receive a similar level of care that would be provided to other racial groups with the same health conditions. In the most extreme circumstances, some may wonder if their lives matter at all, or if they will ultimately be sacrificed—particularly during these times of scarcity and fear. As a result, many (although not all) enter the health care system with deep mistrust; this mistrust may manifest as challenging patient-provider interactions, and lead to care plan failure or perpetuate the cycle of poorer outcomes.

These are difficult, deep-seated issues, and will take larger societal involvement to address. Yet, one of the core issues at the micro level is trust—and this is where palliative care can truly make an impact.

Where Does Palliative Care Fit In?

Globally, palliative care is grounded in health equity principles because the goal is to maximize quality of life for people living with serious illness, regardless of age, stage of illness, gender, race, ethnicity, etc. This is achieved through a comprehensive assessment that considers all aspects of care, including cultural and ethical; developing goals and a plan of care in partnership with patients and families; and effectively managing physical and psychological symptoms and providing support to address other sources of suffering. Specifically, Domains 6 and 8 of the National Consensus Project (NCP) Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th Edition, highlights palliative care’s responsibility to address cultural aspects of care as part of a holistic intervention. Palliative care teams must: 1) ensure equitable, culturally humble/competent/sensitive care in patient and family interactions; and 2) identify opportunities to address the larger forces, structures, and systems that contribute to health and health care inequities.

Palliative care’s core functions have not changed in the context of COVID-19. In fact, building relationships of trust, helping patients and families know what to expect, developing informed goals of care, and managing symptoms are more necessary than ever. What has changed are the ways in which palliative care teams can deliver this care: largely remotely by telephone or tablet, in the context of resource scarcity, and with even more stretched staff than usual (leading to burnout). These factors may force teams to identify efficiencies with regards to provision of the comprehensive interdisciplinary palliative care intervention. However, identifying and addressing the cultural aspects of care cannot be one of the “shortcuts”—particularly given the already disproportionate impact that COVID-19 is having on communities of color.

Practically, this means that palliative care teams must continue to prioritize developing trust with patients of color and their families and developing socially- and culturally-conscious care plans. Palliative care specialists already have the training and tools to address health inequities through high-quality patient/family-provider interactions; however, sustaining this excellent care (particularly in the context of a pandemic) requires both practice and vigilance. Here is a reminder on considerations prior to and during patient interactions:

- Prior to the Interaction. All health care professionals, including palliative care specialists, must assess their preconceptions about race, ethnicity, gender, social class, etc. This assessment must include a critical examination of their implicit bias, which is defined as a judgment or behavior that results from subtle cognitive processes on the subconscious level. Health care professionals must also examine their own assumptions for treatment based on their priorities, goals, and values. Patients’ treatment preferences may be informed by broader cultural considerations, such as greater orientation towards the collective or deep-rooted concerns about inequity; the latter is particularly relevant given the new or expanded traumas associated with COVID-19. And yet even providers who have spent a great deal of time reflecting on these cultural considerations may find themselves slipping into old patterns of thinking or over-generalizing. Therefore, self-assessments must be continuous and grounded in cultural humility.

It is also critical to remember no community is homogenous. Thus, even as health care professionals consider the larger cultural context, they must recognize that each person is an individual with their own history, personality, and preferences. The practice of individuation—focusing on specific information about each individual to inform decision-making—has been shown to reduce implicit bias. Fluency in the tenets of trauma-informed health care can also be particularly beneficial in this effort. This approach takes the perspective of “What happened to this patient?” rather than “What is wrong with this patient?” Adopting this mindset prior to the visit can prime providers to probe more deeply during the patient interaction and better connect historical and social/environmental factors to the illness—all of which create a more detailed portrait of the individual person.

By marrying the contextual and individuated perspectives of the patient, providers are better equipped to establish rapport, navigate unexpected or difficult responses during goals of care discussions, and develop successful care plans.

This assessment must include a critical examination of their implicit bias, which is defined as a judgment or behavior that results from subtle cognitive processes on the subconscious level.

- Cultivating Trust. As part of the comprehensive assessment, it bears repeating that health care professionals MUST believe patients of color when they report pain and other symptoms, and communicate that belief back. This is integral to developing or restoring trust in the patient-provider relationship. Initiating the goals of care discussion should prioritize asking questions about what matters most to the patients and what their fears are. It may be that palliative care teams rely more heavily on the social workers and chaplains to initiate such discussions and build rapport during this crisis, so that medical and nursing professionals can address physical symptom management. However, even the most experienced health care professionals can easily and unconsciously slip into prejudicial assumptions; therefore, all members of the interdisciplinary team (IDT) must continue to practice the discipline of asking questions, empowering patients to respond, and accepting those responses.

The biggest caveat with accepting patient responses in the context of COVID-19 is that the pandemic might require palliative care teams to enter into patient discussions with more of an “agenda” than usual. Transparency, which is always important in building patient-provider relationships, is absolutely critical here. One glaring example of this is the aforementioned resource allocation protocols. Palliative care teams simply might not be able to honor patient preferences due to resource scarcity. There is no easy way around this. The only way through is to be transparent with the patient and family about the circumstances. In these instances, palliative care teams must reinforce that treatment decisions are not made based on the patient’s “worth”. The patient is valued and their life matters—COVID-19 and society’s inadequate response has created demands for resources that are too great to overcome. - Developing Appropriate Care Plans. Palliative care teams—particularly doctors and nurses—must continue to be vigilant about developing practical treatment plans that consider the social determinants of health. Not only does this include previous factors such as food, housing, transportation, family/caregiver support, health care/prescription affordability, health literacy, etc.; but it must now address COVID-19-related factors such as the need for continued physical distancing, lack of personal protective equipment, drug shortages, and a crumbling economy. It is critical for doctors and nurses to maintain this lens and develop realistic care plans; otherwise the social workers and/or case managers who often implement these plans are destined to fail.

Beyond the individual patient/family interaction, Domains 6 and 8 of the NCP Guidelines highlight the field’s ethical obligation to address larger health care inequities. Part of this can be achieved by reviewing your own program’s data for any variances in outcomes based on patient characteristics. Sample issues to look out for could include whether patient and family satisfaction or symptom intensity scores for your program differ based on race/ethnicity, or if a greater percentage of Medicaid patients use the emergency department or hospital than those who are commercially insured. Looking at your data critically can help highlight potential systematic issues, and put you on a path to addressing them.

Another opportunity to support health care equity is expanding palliative care to underserved communities. Research suggests that, within institutions that offer palliative care, use is relatively equitable across populations; the challenge is that underserved communities are less likely to have access to any palliative care professionals. Therefore, palliative care teams might explore opportunities to extend their reach, such as the efforts undertaken by the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB)’s Center for Palliative and Supportive Care (examples here and here). Palliative care programs should also continue to explore new telehealth flexibilities (and advocate to retain these flexibilities), while remaining conscious of the inequities that exist with these modalities. And teams can lead or support public awareness efforts promoting the benefits of palliative care in underserved communities.

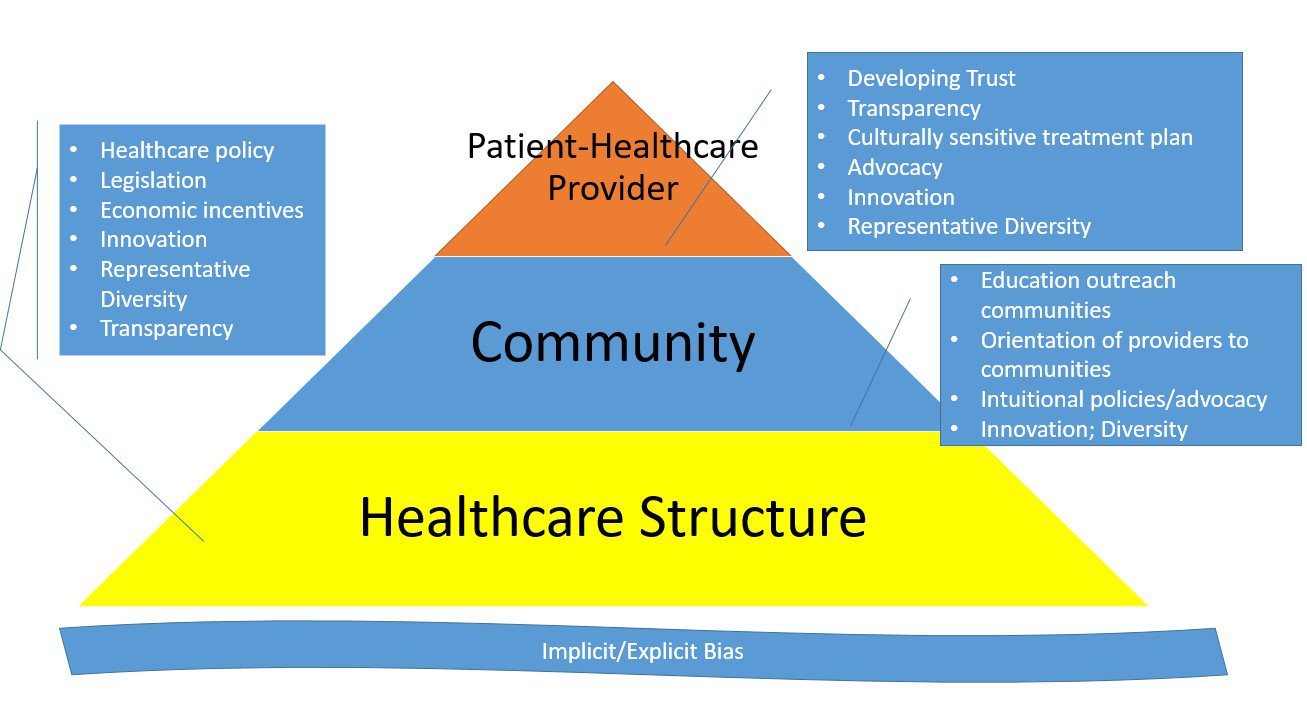

At a higher level, as the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic subsides, the health care system is both adjusting to a “new normal” and preparing for subsequent waves. This presents a significant opportunity for palliative care leaders to advocate for more equitable policies, processes, and practices in their organizations and the broader society. Activities can include working with organizational leadership on COVID-19 emergency preparedness and response efforts that prioritize health equity; serving on committees to improve resource allocation guidelines for future waves; and—for allies—ensuring that leaders of color are seated at those tables and supporting efforts to center their voices. And palliative care experts can participate in national conversations and initiatives to support health equity, including addressing incorrect narratives and the reality of implicit bias head-on and supporting data collection efforts on health care disparities in COVID-19 treatment. The following image highlights opportunities to address health and health care inequities at all levels.

CAPC Tools and External Resources

CAPC is committed to supporting the efforts of palliative care teams to deliver equitable care across patient populations. To that end, we have developed and/or compiled several tools to support your efforts.

Preparing for the Interaction

The more internal work one can do prior to the interaction, the better the discussions will go. Key aspects of preparation include assessing for and managing implicit bias, anticipating patient circumstances and recent encounters (see previous images) without locking in on pre-judgements, and developing a framework of cultural sensitivity/humility/competence. Relevant resources include:

- CAPC Master Clinician: Managing Implicit Bias and Its Effect on Health Care Disparities

- CAPC Blog: Implicit Bias and Its Impact on Palliative Care (Part One)

- CAPC Blog: Implicit Bias and Its Impact on Palliative Care (Part Two)

- CAPC Blog: Be Prepared: Implementing Advance Care Planning Across Cultures

- CAPC Blog: Lessons of Trauma-Informed Care

- NCP Guidelines: Domain 6 (“Cultural Aspects of Care”) and Domain 8 (“Ethical and Legal Aspects of Care”)

Facilitating Difficult Discussions

There are no magic words or algorithms that will ensure these discussions go perfectly—this is true even for patients who have not experienced significant trauma and/or health care inequities. However, palliative care professionals can benefit from reviewing sample language to better respond to concerns about inequity. Fluency in these domains will help build trust, and enable providers to recognize when patient concerns or resistance might be unrelated to the specific topic at hand. Relevant resources include:

Expanding Palliative Care Access from a Health Equity Perspective

Palliative care teams should continuously search for broader opportunities to improve care for underserved populations. Relevant resources include:

- CAPC Discussion Group: Palliative Care for Underserved/Vulnerable Patients

- CAPC Tool: Equitable Palliative Care Access in COVID-19

- CAPC Blog: How to Increase Awareness and Reduce Gaps in Palliative Care for Minorities

- CAPC On-Demand Webinar: OASIS: A Replicable Model to Support Communities of Color in Accessing and Utilizing Palliative Care

- CAPC Blog: Five Strategies to Expand Palliative Care in Safety-Net Populations

- CAPC On-Demand Webinar: Caring for Vulnerable Populations with Serious Illness

External COVID-19-Related Health Equity Resources

In addition to palliative care-specific resources, several organizations have developed excellent materials to address health and health care inequities in the midst of COVID-19. These include (but are not limited to):

- AMA COVID-19 Health Equity Resources

- Race and Social Justice Initiative

- NAACP Coronavirus Equity Considerations

- APHA COVID-19 and Equity

- Racial Equity: Getting to Results

As CAPC develops new and/or compiles existing resources to support palliative care teams in addressing inequities during the pandemic, we want to hear from you. Please complete our COVID-19 health disparities survey, to share what tools and resources would be most helpful to you.

Conclusion

While supporting people at risk for disparities, and who have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19, is the responsibility of ALL health care professionals, palliative care plays an especially significant role in this work. First and foremost, palliative care teams can support these patients by providing respectful, person-centered, culturally appropriate care. This requires practicing cultural humility in assessing one’s own implicit bias; considering patient and family circumstances (including prior trauma and the broader cultural context) prior to the interaction; using the comprehensive assessment to support patient individuation, identify sources of suffering, and build or restore trust; and developing socially/culturally conscious care plans. Second, palliative care teams are well positioned to identify opportunities to expand access to underserved communities (especially with expanded use of telepalliative care) and participate in larger organizational and policy initiatives to support health equity. CAPC looks forward to partnering on these efforts and welcomes any feedback on what resources would be most beneficial.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the following people who contributed their expertise and reflections to inform the writing of this blog:

- Karen Bullock, PhD, LCSW, APHSW-C, Professor and Head of the School of Social Work at North Carolina State University

- Sandy Cayo, DNP, FNP-BC, APRN, New Jersey Hospital Association

- Kimberly A. Curseen, MD, FAAHPM, Director of Outpatient Supportive Care, Emory Palliative Care Center