Be Prepared: Implementing Advance Care Planning Across Cultures

Rona is a Palliative Care Nurse Practitioner with the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC), a non-profit Tribal health organization designed to meet the unique health needs of Alaska Native and American Indian people living in Alaska. ANTHC provides world-class health services: comprehensive medical services at the Alaska Native Medical Center; wellness programs; disease research and prevention; rural provider training; and rural water and sanitation systems construction.

Historically, Advance Care Planning (ACP) has been a difficult topic to address with Alaska Native people. While the exact reasons are unknown, cultural barriers of geography, language, and health literacy are among some of the challenges. These barriers are compounded by a state Advance Directive that is written in confusing legal-jargon, and typically presented during high stress times, such as a hospitalization or surgery.

Advance Care Planning Helps Alaskans Prepare for the Unexpected

High-risk jobs, extreme weather conditions, and active lifestyles make unintentional injury the third leading cause of death for Alaskans. Additionally, Alaska Native people are two times more likely than Caucasians to be injured, despite representing less than 16 percent of Alaska’s total population. Many injuries occur in rural areas, far from diagnostic medical and intensive care; transportation from a remote village to our tertiary hospital in Anchorage may take hours or days depending on medevac availability and weather conditions.

Delays in treatment can have lifelong consequences, rendering many without capacity to make their own medical choices.

Delays in treatment can have lifelong consequences, rendering many without capacity to make their own medical choices. In the absence of information about patient preferences, the default is often an escalation of aggressive medical care with little consideration about post-hospitalization function and quality of life. Despite rehabilitation, many have complex medical needs that make it impossible for them to return back to their families or home communities—which, to some, is a fate worse than death. ACP is critical to help our Alaska Native patients and families advocate for the medical care they want and protect them from care they are trying to avoid.

Responding to a Need: Communicating Advance Care Planning Across Cultures

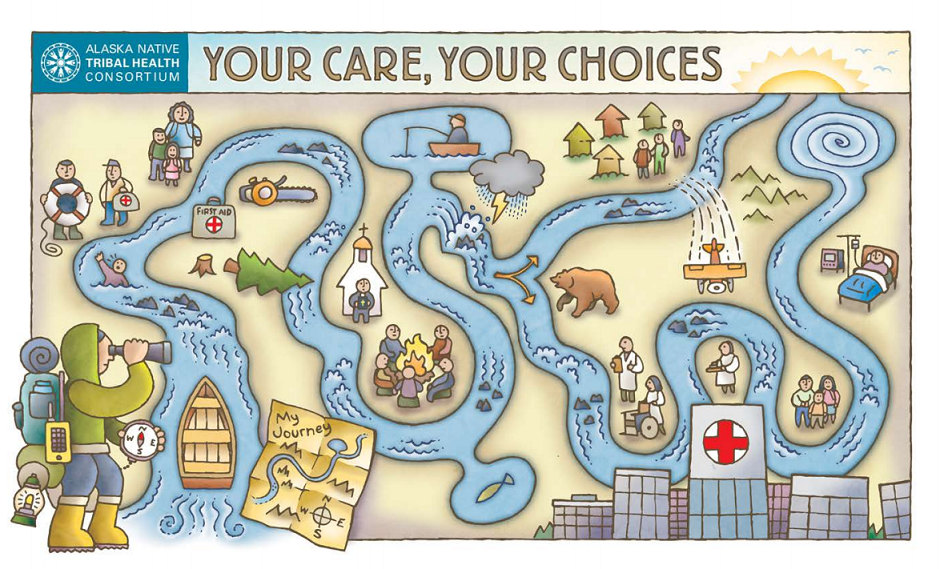

Based on data from multiple statewide needs assessments, ACP and advanced communication skills training are the most requested interventions by Alaska’s health care providers, in both urban and rural settings. In response to this need, the ANTHC palliative care team has developed easy-to-use tools and resources to promote ACP discussions: a simplified Advance Directive; a culturally-tailored Conversation Guide; and a bright, interactive Wellness Map, which are free to download from our website by professionals and the public.

ACP and communication skills training are the most requested interventions by Alaska’s health care providers.

The Conversation Guide doubles as patient education—as well as a facilitator’s guide—with open-ended questions throughout to assist health care providers with facilitating ACP conversations. It also includes short vignettes that recognize and honor the storytelling cultures of the Alaska Native people, while highlighting the relevance of ACP at any point across the lifespan.

The Wellness Map was developed to lead an individual through a visual representation of a journey down the river of life. The river guide symbolizes a medical provider, a caregiver, or perhaps even the patient; the boat–their support system; the rocks–perceived barriers; the person with the life ring–their health care agent; and the map–their advance directive, which helps the guide to navigate. The imagery woven throughout the map provides many opportunities to broaden and deepen the conversation. It is intentionally pictorial, without words, so that each individual can define their own story, unencumbered by assumptions.

The map is useful for simply and clearly capturing what is important without the jargon, “death foreshadowing” or formality that can stymie these conversations. By giving space and listening to the life experiences of an individual, culture is no longer a barrier, but rather a context for providing the best possible care for the Alaska Native people.

By giving space and listening to the life experience of an individual, culture is no longer a barrier.

If It’s Not Documented, It’s Not Done: Measuring What Matters

While ACP tools are useful, our most important work has been creating and standardizing systems and processes that support the conversation. Integrated quality metrics within electronic health records (EHRs) track the efficacy of interventions, and newly created data fields capture the date when an ACP conversation is introduced. Automatic triggers prompt providers to reintroduce ACP and/or review documents annually with patients to ensure that advance directives are aligned with the current goals of care. Staff have been trained to use the ACP tools, as well as locate and appropriately scan documents within a designated folder, which is accessible from any EHR summary page—where advance directives are clearly documented for easy and immediate identification.

In addition, ACP conversations are now initiated in primary care beginning at age forty, at the same time as routine health screenings. A widespread public relations campaign throughout the hospital campus uses posters, banners, lapel buttons, brochures, and health education TV channels to encourage patients to voice their wishes. The campaign theme is a mantra that all Alaskans can identify with before stepping out into an unpredictable wilderness: “Be prepared.”

Final Thoughts, Wishes, and Hopes for the Future

Ironically, as I make final edits to this blog post, I hear the dreaded chimes overhead on the hospital intercom calling a Code Blue to the Critical Care Unit (CCU). I breathe a quick sigh of relief as I scan the EHR roster and determine it is not one of the patients that our palliative care team has been following. But my next breath is a deep one, with an ominous feeling that penetrates my body like a cold chill. I can mentally visualize the disarray of a code on an 87 year-old elder who arrived via emergency medevac from a remote village in Alaska, less than one hour ago.

I can hear the crescendo of noise moving to the bedside—the beeps, bumps, voices, and shuffles of people and equipment. I feel the adrenaline of a highly trained staff focused on saving a life. I can see the frightened faces of a loved one as they watch blindly from the corner of the room without control—I am not there, but I am a witness.

This patient’s goals, values, and preferences are not documented within our EHR. I do not know his story. I only hope that others do, and that we are honoring his wishes. It is this hope that continues to drive the work of our team, so that one day all Alaska Native voices are heard, and medical wishes known and honored, across every health care setting.

It is this hope that continues to drive the work of our team, so that one day all Alaska Native voices are heard, and medical wishes known and honored, across every health care setting.