Acknowledging Barriers and Implementing Strategies to Reach Black People with Serious Illness

Introduction

A growing body of research demonstrates disparities in access to palliative care services, care quality, and outcomes for Black patients living with a serious illness. The need for decisive and sustained action to reduce health care disparities is not new; however, it was elevated in recent years by three high-profile murders and the devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Black (as well as Latino and American Indian/Alaska Native) communities.

In response, CAPC launched Project Equity, an initiative to create tools for meaningful change in the care of those in traditionally oppressed communities living with a serious illness. One of the first efforts in this project is “Equitable Access to Quality Palliative Care for Black Patients: A National Scan of Challenges and Opportunities.” In its simplest form, this scan seeks to answer two questions:

- What goes wrong in health care for Black people living with a serious illness?

- What interventions have been tested to address disparities in the care of Black people living with a serious illness?

Interviews with subject matter experts (SMEs)

As part of this scan, CAPC staff conducted 25 interviews with 27 subject matter experts (SMEs) in health equity and serious illness from August to October 2021. The SMEs included clinicians, researchers, policy experts, payment experts, and six people who identified as patients or caregivers (although several professionals also shared their personal experiences as patients and caregivers). In addition, we interviewed the 12 members of CAPC’s Health Equity Project Advisory committee. We thank the National Patient Advocate Foundation for their help recruiting patient and caregiver interviewees.

Interview themes fell under the following categories:

- Barriers to accessing palliative care for Black patients living with serious illness, both historically and during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Strategies for engaging Black patients (and their caregivers)

- Promising interventions to improve care for Black patients living with a serious illness and their families

- Policy levers to address systemic racism and barriers to quality health care access

- Measurement priorities to ensure that health equity work leads to meaningful improvements

This blog provides highlights from the first two themes, and lays the foundation for future publications on CAPC’s interview series.

Barriers to equitable care

Prolonged focus on barriers creates a tendency to “admire the problem” without working toward solutions. However, we started our interviews here in order to:

- Better understand the scope and scale of the challenges that Black patients with serious illness face;

- Identify root causes of disparities so that, as we encounter promising interventions and develop recommendations, we can map them to the factors that will make an impact; and

- Cultivate an awareness of patient and family experience that will guide CAPC’s work.

Interviewees described many barriers to receiving palliative care for Black patients living with a serious illness. These barriers ranged from individual/interpersonal to systemic and structural; those that derive from historical oppression to new barriers being erected today; those specific to health care and those that stem from social determinants of health.

"Interviewees described many barriers to receiving palliative care for Black patients living with a serious illness."

Interviewees cautioned CAPC to consider health care delivery beyond access to palliative care (for example, care delivered to Black patients with serious illness in primary care settings). We acknowledge the wisdom of this advice—while we firmly believe that equitable access to high-quality palliative care is a right, patients and families interact with myriad care settings and care providers, and all of these interactions contribute to the experience of serious illness. While this article takes a focus on specialty palliative care as a starting point for CAPC’s Project Equity initiative, future activities will expand the focus beyond care delivered by palliative care specialists.

What must go “right” for Black patients to access palliative care

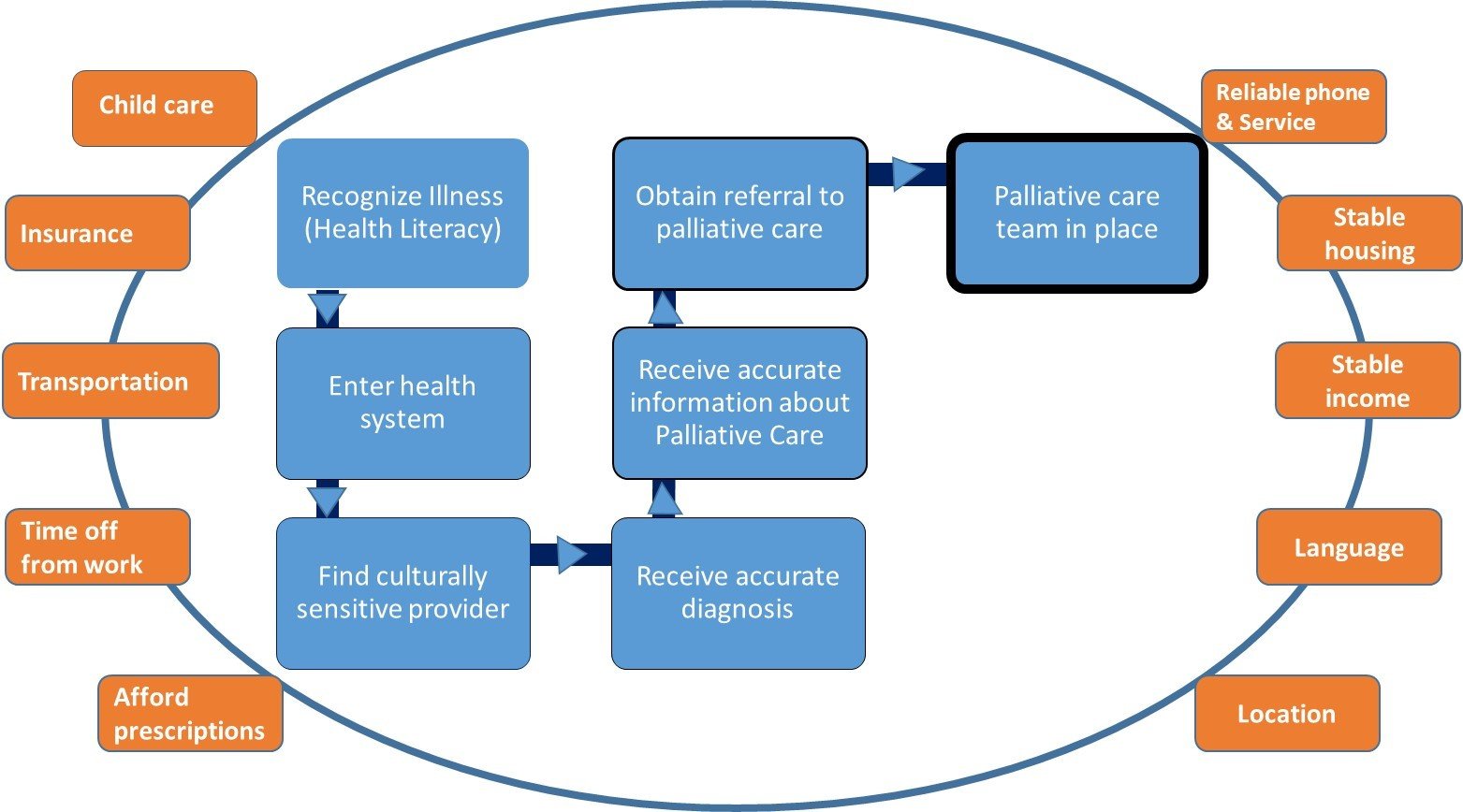

Interviewees identified the number of things that must go “well” for a Black patient with serious illness to receive palliative care (see Figure 1). While not an exhaustive list, we heard the need to overcome structural, social, and cultural barriers. These included the patient’s ability to recognize the symptoms of a serious illness and seek care, enter and navigate a fragmented and complex health care system, find the right provider, get an accurate diagnosis, receive a palliative care referral, and see the team. Whether or not palliative care specialists are available can come down to an accident of geography.

"[Barriers] included the patient’s ability to recognize the symptoms of a serious illness and seek care, enter and navigate a fragmented and complex health care system, find the right provider, get an accurate diagnosis, receive a palliative care referral, and see the team."

Interviewees highlighted that obstacles to health care—including but not limited to palliative care—can also include basic health literacy, language, vocabulary, ability to take time from work, need for child/dependent care, transportation, and the costs of care. For palliative care teams, this means that taking steps to understand the barriers to care facing the patients in one’s community—and taking steps to address barriers—is critical to ensuring equitable access to palliative care services.

A starting list of what must go "right" for Black people living with a serious illness

While many of the barriers discussed were systemic, some interviewees also highlighted the behaviors of individual clinicians. Interviewees noted implicit and sometimes explicit bias among health care clinicians, including a failure to see Black patients as co-equals. This paves the way for clinicians to make stereotypical assumptions about patients, and those preconceptions inform care – including whether or not patients are referred to palliative. Interviewees pointed to the problematic nature of claims such as “I don’t see race” or “we treat all patients the same,” since these stances negate the impact that race has on the experiences of Black patients, and interfere with an important opportunity to tailor care.

Breaking through obstacles

SMEs emphasized that many Black patients and their families have grown to mistrust the health care system due to systemic racism that is embedded in our health care system. Several interviewees cited the Tuskegee Experiment and Henrietta Lacks, and others saw the racial disparities in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality as a watershed event unto itself. One interviewee observed, “It is difficult to change the narrative of systemic racism, health disparities, and exclusion from palliative care when: a) direct experiences are not in the distant past; b) there are so few current/compelling examples that care has changed.”

Our interviewees identified strategies that palliative care teams can implement to better engage, support, and earn trust among Black people living with serious illness and their families. Key themes included timing, messaging, and the use of trusted messengers to convey the benefits of palliative care.

Timing

Interviewees emphasized that patients should not hear about palliative care for the first time in the context of an emergency. The need for pre-education has been particularly significant during the COVID-19 pandemic, given the rapid illness progression of the virus, the pronounced disparities in incidence and outcomes based on race and ethnicity, and a heightened landscape of misinformation and mistrust. Although we often state the goal of introducing palliative care at the point of diagnosis, interviewees noted that it would be preferable to learn about its benefits—ideally multiple times—during usual/primary care or even in communities settings (e.g. religious institutions, community centers, etc.).

Messaging

Interviewees noted that the phrase “palliative care” does not resonate with many Black people living with serious illnesses. While this issue is not unique to Black patients, to date there has not been enough research and testing to identify messages that would better engage different populations. In the meantime, SMEs suggested using simpler messaging that focused on what palliative care does, rather than terminology.

One interesting line of discussion also focused on the need for market research to analyze the components of palliative care messaging by patient demographic. For example, words such as “help” and “support” that are commonly used to describe palliative care may land differently based on the audience. SMEs shared that many Black patients have spent their lives fighting inequity and disparities and, as a result, may consciously or unconsciously uphold concepts like independence and self-reliance as defense mechanisms in their interactions with the health care system. For some patients, asking for help—particularly from individuals outside of their community—signals weakness or feels like a threat to their dignity.

Trusted messengers

For interviewees, the “when” and “what” of palliative care messaging was far outweighed by the “who”. SMEs focused on the need for person-led, high-touch outreach, and stated that for many Black patients living with serious illnesses, palliative care education is best received from peers and credible leaders who resemble their audience. Several SMEs identified faith leaders as the best potential partners in messaging efforts. However, a few cautioned against overburdening faith communities during an already challenging COVID era. Some suggested engaging other community partners such as local businesses (e.g., barbershops, beauty salons) to “meet people where they are.” There was even a discussion about partnering with local grocery stores as a component of a holistic community intervention.

Some SMEs referenced other modalities for message delivery. Recent public health messaging has relied heavily on the internet and virtual communication; however, given digital inequities, it is important to utilize other media such as print media, radio and television spots, bus ads, etc.

"The best way for palliative care teams to 'break through' and build credibility is to deliver consistently on the promise of better care."

As SMEs proposed strategies to deliver the message about palliative care and its benefits further upstream, we learned from these discussions that there is no fast track to building trust. Given the barriers described above, most health care providers are working against a trust deficit. Therefore, the best way for palliative care teams to “break through” and build credibility is to deliver consistently on the promise of better care. To provide individualized, culturally competent, unbiased care does not happen by accident. It requires training, practice, and intention.

Conclusion

Our discussions with these subject matter experts provided critical context for the larger project on “Equitable Access to Quality Palliative Care for Black Patients.” A foundational challenge—as heard in the interviews and in responses from CAPC’s recent national questionnaire—is that not all clinicians have a comprehensive understanding of systemic racism and its impact on health care and outcomes for Black patients. Everyone is entering this discussion from a different starting point, but knowledge is power. Understanding the historical basis of present-day inequity helps clinicians to recognize the disparities around them, and to take action. Without this understanding, we risk perpetuating the cycle of harm.

Hearing first- and second-hand about the barriers that Black people living with a serious illness and their families face, as they try to access palliative care, reinforces why efforts to advance health equity are vitally important. As the CAPC team proceeds—guided by our Equity Steering Committee and in partnership with other experts across the country—these interviews will continue to guide our thinking and efforts to identify promising interventions to address disparities, develop technical assistance to scale these models, and build long-term health equity strategies for our field.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the following people who contributed their expertise to inform the writing of this blog:

- Dr. Marcia Lowe, PhD, MSN, BSN, RN-BC, 2nd VP, Membership Chair, and End of Life Committee Chair, National Black Nurses Association (NBNA)

- Diane Deese, Vice President Community Affairs, VITAS Healthcare

- Gloria Thomas Anderson, PhD, LMSW; Karen Bullock, PhD, LCSW, APHSW-C; Rev. Cynthia Carter-Perrilliat, MPA; Sandy Cayo, DNP, FNP, BC; Komal Chandra, PhD, MMH; Zara Cooper, MD, MSc, FACS; Diane Deese; Faye Hollowell, BS, MTh; Jacquelyn Lambert-Davis, DNP, RN; Marcia A. Lowe, PhD, MSN, BSN; Elder Angela Overton, MDiv.; Danetta E. H. Sloan, PhD, MSW, MA

We thank The Commonwealth Fund, The John A. Hartford Foundation, and The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations for their generous support of this initiative.

Be the first to read articles from the field (and beyond), access new resources, and register for upcoming events.

SubscribeEdited by Melissa Baron. Clinical review by Andrew Esch, MD, MBA.