New Payment Models Provide Opportunities to Enhance Care in Nursing Homes

Life for nursing home residents, their families, and the staff who care for them has been completely disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. There are multiple heartbreaking descriptions of outbreaks in facilities, and the statistics on the numbers of deaths in nursing homes is sobering. Investing in best practices to improve care for nursing home residents has never been more urgent.

High Need and Costs for Long-Term Care

Nursing home residents have a high burden of cognitive impairment, functional impairment, and serious illness; half of all people who receive care in a nursing home have a diagnosis of dementia. They require support for basic activities of daily living, such as bathing, getting to the bathroom, or feeding themselves, and generally move there due to the inability to live independently, in a safe environment. There are nearly 1.7 million beds in the over 15,600 nursing homes in the United States.

Even though long-term nursing home care is needed for this population, Medicare only pays for “post-acute care” in nursing homes – the days immediately following a hospitalization.

Even though long-term nursing home care is needed for this population, Medicare only pays for “post-acute care” in nursing homes – the days immediately following a hospitalization. After those days are exhausted, residents and their families must pay out-of-pocket for care; most people do not have private long term care insurance that will cover nursing home care. This type of care is very expensive while paying out-of-pocket – most long stay residents become eligible for (means tested) Medicaid coverage over time, if they were not eligible for Medicaid on admission. On average in the United States, a private room in a nursing home costs $8,365 per month, and semi-private room costs $7,441 per month. Medicaid, the ‘safety net’, will pay for nursing home room and board. Thus, the nursing home industry is largely publicly financed, through state and federal dollars.

Why Hospital Transfers of Nursing Home Residents Became a Hot Topic

Concerns about safe transfers of nursing home residents have been heightened during the pandemic, however, this has been an area of focus for years. Pre-COVID, the issue of hospital readmissions and overall transfer rates of nursing home residents has particularly caught the attention of policymakers, researchers, and the health care industry.

Hospitalizations and the post-acute care days that follow, are covered by Medicare. An Inspector General report found that about 25% of nursing home residents were transferred to the hospital in 2011, at a cost of $14.3 billion to Medicare. They also noted that there was wide variation among nursing homes in transfer rates.[1] Research has demonstrated up to 40% of these nursing home to hospital transfers may be potentially avoidable.[2]

Despite the substantial costs borne by the Medicare program for hospital transfers, efforts to incentivize reduction of hospitalization rates have been hamstrung by financial misalignment. Medicare has introduced financial penalties for nursing home readmissions, as well as a publicly reported quality metric for readmissions.[3] Reduction of hospital transfers, however, requires investment in the level of daily care, and resources in nursing homes – “enhanced" care that is not paid for through Medicare.

Despite the substantial costs borne by the Medicare program for hospital transfers, efforts to incentivize reduction of hospitalization rates have been hamstrung by financial misalignment.

If a resident becomes sicker, requiring more nursing care, nursing homes do not receive any additional dollars to care for the resident. However, if that resident transfers to the hospital and comes back after a three-day hospitalization, the facility receives the much higher Medicare post-acute care payment rate, creating a direct financial incentive for the nursing home to transfer sick residents to the hospital. Efforts to change these incentives, however, have raised concerns about the ability of nursing facilities to provide appropriate care to sick residents.

Seeking Clinical and Financial Solutions

In response to concerns about unnecessary hospital transfers, in the fall of 2012, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) funded 7 clinical demonstration projects, designed to reduce avoidable hospital transfers of long stay nursing home residents. Each project site designed a clinical model to provide enhanced care for nursing facility residents at risk of potentially avoidable hospitalization in nursing homes. The project that my team and I lead, named OPTIMISTIC (Optimizing Patient Transfers, Impacting Medical Quality, and Improving Symptoms: Transforming Institutional Care), has been running continuously since 2012 in central Indiana, in the following phases:

- Phase 1 (2012-2016), tested clinical models run by 7 sites across the country. We had the opportunity to place additional resources in nursing homes, with a goal of reducing hospitalizations.

- Phase 2 (2016-2020), building on Phase 1, CMMI is now implementing the 2nd phase, which tests a payment model where nursing homes and clinical providers can bill for acute care provided in the nursing home. In our original facilities, we continue to fine-tune our clinical model in addition to the financial model; a second group of facilities has access to the payment codes only. There are a total of 40 facilities currently participating in the OPTIMISTIC project.

Role of Enhanced Staff

In the OPTIMISTIC model, we embed RNs into nursing homes and support them with a program of training in geriatrics and palliative care, which we have developed. Our RNs have a novel role in facilities: they support and mentor nursing home staff in best clinical practice, respond to changes in condition using structured tools, support residents in place through episodes of acute illness, perform detailed root cause analyses on transfers that do occur, and facilitate advance care planning conversations with residents and their families. In addition to these RNs, OPTIMISTIC NPs, also supported by the grant funding, cover several facilities and are available to provide additional clinical support to residents and do detailed transition visits following a hospitalization, working collaboratively with primary care providers.

Results Thus Far

We have had exciting results so far – in Phase 1 of the project, an external evaluator found that OPTIMISTIC facilities had reduced avoidable hospitalizations by one-third, compared to control group facilities. Even prior to the release of results by the evaluators of the demonstration project, our team had been fielding calls from nursing homes interested in implementing OPTIMISTIC.

In Phase 1 of the project, an external evaluator found that OPTIMISTIC facilities had reduced avoidable hospitalizations by one-third, compared to control group facilities.

As we are in the final year of Phase 2, we are excited to report on these results once complete.

Next Steps: Implementing a Proven Care Model

In March of 2019, with the support of my colleagues, I founded a health care start-up business, Probari (formally known as Care Revolution, Inc.), designed to disseminate the successful OPTIMISTIC clinical care mode in nursing homes across the country. We have a model that works – one that provides structured support for long stay residents, their families and nursing home staff to promote high quality, person-centered care in place.

Before launching, the biggest questions were:

- Who will buy this?

- What is our business model?

- Who wouldn’t want additional, well-trained staff deploying evidence-based protocols in their building – but is it compelling enough to succeed in the marketplace?

- In the OPTIMISTIC demonstration project, the staff are supported by the project funding. Is there a payment model to support the additional staff and staff training?

Determining Timing

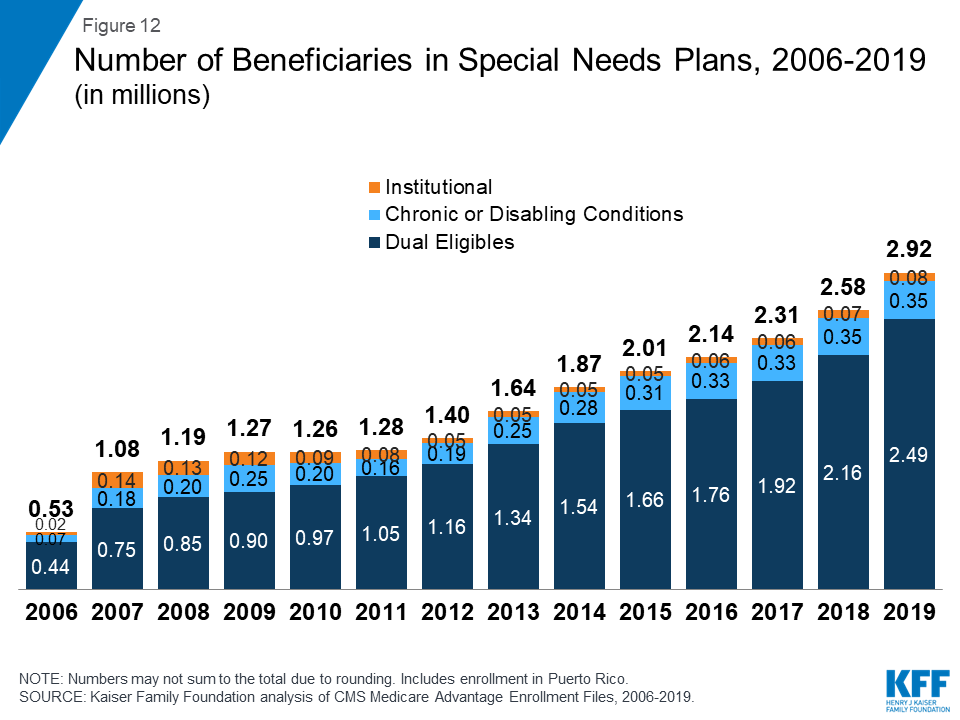

I believe that now is the right time and that we will succeed in disseminating this care model primarily due to current trends in payment that incentivize value-based care. Institutional Special Needs Plans (I-SNPs) are shaking up the nursing home market. For more background, I-SNPs are a category of Medicare Advantage (Medicare managed care) plans targeting long stay nursing home residents. Since CMS made I-SNPs a permanent category of Medicare Advantage plans in January 2018, there has been tremendous growth in the number of new plans. I-SNP providers receive a per member, per month capitated fee for each Medicare enrollee into the plan up front and then are responsible for the total Medicare costs (including any hospital costs) for the resident.

Growth in Institutional Special Needs Plans (I-SNPs)

As I-SNPs form, entities are looking for ways to embed additional staff in facilities, tools, and strategies to improve acute care in place and reduce hospital transfers. Participation in I-SNPs provides a direct financial incentive to reduce hospital transfers, as well as capital through the per-member per-month fees that can be spent on additional staff or other resources. The Probari team is already partnering with forward-thinking companies to implement this care model, including those interested in participating in value based payment structures. In addition to I-SNPs, health system-nursing home network partnerships, particularly in the context of Accountable Care Organizations, provide avenues for investment in enhanced clinical care.

OPTIMISTIC is a $30.3 million project, which has generated substantial experience with implementation of an enhanced care model in the nursing home setting. Probari aims to leverage this into improving care for residents in nursing homes across the country, by training and supporting specialized staff who connect vulnerable residents and families with the care they want and need. The challenges of COVID-19 have exposed multiple areas of our health care systems that require enhancement. The Probari care model is proven to support nursing homes in delivering high-quality care in place.

Footnotes

-

https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-06-11-00040.pdf

-

Walsh, E., Freiman, M., Haber, S., Bragg, A., Ouslander, J., & Wiener, J. (2010). Cost drivers for dually eligible beneficiaries: Potentially avoidable hospitalizations from nursing facility, skilled nursing facility, and home and community-based services waiver programs. CMS Contract No. HHSM-500-2005-0029I.

-

Carnahan, Jennifer & Unroe, Kathleen & Torke, Alexia. (2016). Hospital Readmission Penalties: Coming Soon to a Nursing Home Near You!. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 64. 614-618. 10.1111/jgs.14021.