How to Help Relieve Constipation in Patients with Serious Illness

It’s not an exaggeration to say that constipation is one of the biggest and perhaps most pervasive complaints among patients with serious illness. Up to 70% of patients with serious or chronic illness experience constipation, yet it often goes unrecognized and undertreated. Why is this?

There is no universally accepted definition of constipation, which is a challenge for recognizing and managing this distressing symptom. That said, the prevention and treatment of constipation are essential to the care of all people living with serious illness. Constipation can significantly reduce quality of life and increase anxiety and costs for patients and caregivers, which in turn results in preventable complications, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations. It’s a tedious cycle that must be disrupted. And clinicians can do just this.

"Up to 70% of patients with serious or chronic illness experience constipation, yet it often goes unrecognized and underrated."

Anticipation, Prevention, Assessment

Constipation is known for its high prevalence among people living with serious illness. Since most serious illnesses are associated with constipation, anticipating that it may become a problem is essential for prevention or treatment so the person living with a serious illness does not experience the complications that come with it.

We know that most serious illness occurs in the context of a multifactorial soup consisting of age, decreased mobility, reduced food/fiber intake, reduced fluid intake, pain, and, of course, pain medication—all contributors to constipation. With this in mind, clinicians can educate patients about prevention techniques, including lifestyle changes such as improved nutrition and hydration, and supporting and encouraging increased mobility. Another important prevention technique is to start a laxative anytime opioid analgesics are used for pain or dyspnea, because they cause constipation through their interaction with opioid receptors in the gut.

That said, a common scenario for most palliative care clinicians is that they inherit or consult on patients well into their serious illness course. Combined with not having consensus on a concise definition, diagnosing constipation is at times challenging. Certainly, abdominal pain, bloating, change in bowel frequency and consistency (including paradoxical overflow diarrhea!), cramping, and back pain would raise red flags. However, we also see more nuanced symptoms due to or related to constipation, such as agitation, fever, and even delirium—especially in patients with cognitive impairment.

"It is important to note that in most patients with constipation, the physical exam is unremarkable; therefore, a routine physical examination does not rule out a diagnosis of constipation."

A detailed, comprehensive assessment and clinical judgment play a huge role in the recognizing constipation. It is important to note that in most patients with constipation, the physical exam is unremarkable; therefore, a routine physical examination does not rule out a diagnosis of constipation.

Since we know the prevalence of constipation, we have to do our best to anticipate and prevent it, and for patients who come to us already symptomatic, we need to look for it and treat it.

How to treat constipation

Without a consensus definition and definite parameters, the question becomes: what’s the best way to treat constipation for a person living with serious illness? The primary objective of preventing and treating constipation is to reestablish comfortable, regular bowel habits and avoid complications such as obstruction or perforation. Education, dietary and fluid recommendations, and non-pharmacologic treatment are first line. However, pharmacological treatment is often necessary.

Pharmacological treatments

Several treatments are available for opioid-induced constipation. Methylnaltrexone bromide (Relistor) is a peripherally acting opiate antagonist that was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in the treatment of opioid-induced constipation in 2008. Other therapies include naloxegol and naldemedine, both of which are approved for treatment of opioid-induced constipation in patients with non-cancer pain. Other options are alvimopan, a treatment approved for treating recalcitrant cases of postoperative ileus, and lubiprostone, which can be used in both patients with cancer and non-cancer pain from constipation.

Laxatives should be used as the first step in the pharmacological management of opioid-induced constipation. And when prescribing an opioid, it is essential to pair it with a laxative to prevent constipation in your patient.

You may not need to go any farther than this, but it’s better to start small and go from there. Laxatives may very well work without requiring more powerful—and more expensive—treatments.

Taking treatment into the home

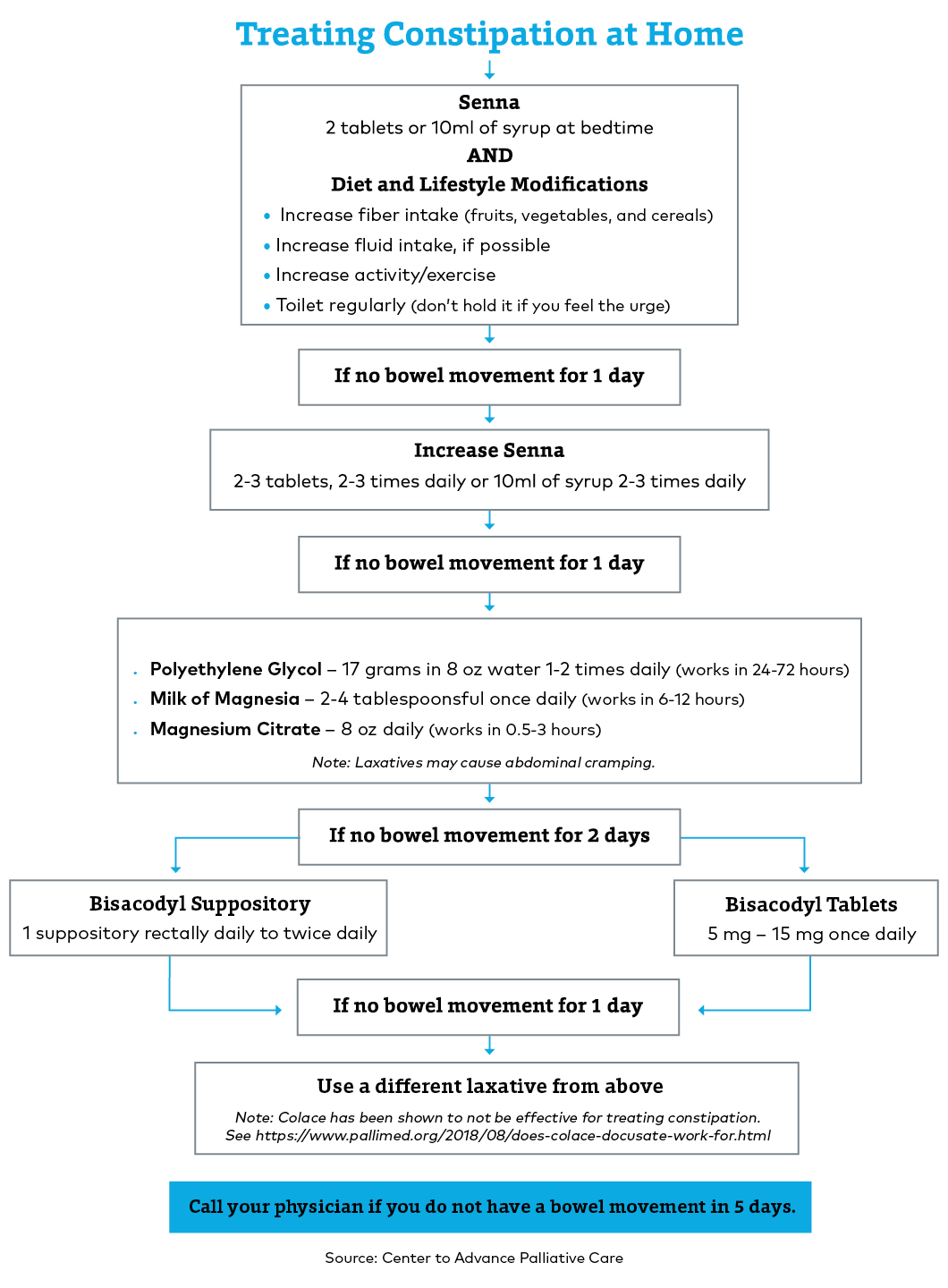

A decade ago, I collaborated with two other palliative care clinicians to develop an algorithm for addressing constipation at home. Our goal was to create an easy tool for patients to understand and follow, ideally giving back some of the sense of control they felt they’d lost. I’ve found that this algorithm works for the vast majority of people.

"Essentially, the algorithm sketches out a plan for our patients so they can take action at home, where they feel more comfortable."

The algorithm starts with diet and lifestyle modifications, as well as a two-tablet dose of senna, a commonly used stimulant laxative. Then, we instruct our patients to wait and see what happens. If they don’t have a bowel movement after one day, we recommend increasing their intake of senna.

Additional steps follow if the patient continues to experience constipation and does not pass any stools. At one point, if there is no progress, the patient can also begin taking an osmotic laxative such as polyethylene glycol (Miralax), magnesium hydroxide, or magnesium citrate.

Essentially, the algorithm sketches out a plan for our patients so they can take action at home, where they feel more comfortable. This empowers them and hopefully also lowers their distress levels while they wait for things to get moving again.

Reassurance as a component of the treatment plan

Constipation is such a common problem among people living with serious illness—particularly those who may be taking opioids for pain relief—that we may develop a tendency to downplay it. We allow it to register lower on our attention scale because we know, as clinicians, that it will eventually resolve.

But ongoing constipation really bothers our patients. Research shows that psychological distress is very real among patients who are affected by constipation. This can even result in “depressive symptoms and anticipatory anxiety related to constipation,” according to the authors of a study in Palliative Medicine. Even in less serious cases, it detracts from their quality of life.

"In my experience, I’ve found that patients need constant reassurance along the way and to know that they will eventually have a bowel movement."

So we do need to address it. In my experience, I’ve found that patients need constant reassurance along the way and to know that they will eventually have a bowel movement. It just may take a little while to find the right solution. Having this reassurance helps their anxiety begin to subside (which, as we know, contributes to constipation). Reassurance is a valuable part of their treatment plan.

As you continue to encounter patients on your palliative care service with complaints about abdominal pain, I encourage you to listen closely to them. The culprit may well be constipation, as it often is, and you can assuage some of their fears by acknowledging their discomfort and suggesting some strategies to alleviate it.

Be the first to read articles from the field (and beyond), access new resources, and register for upcoming events.

SubscribeEdited by Melissa Baron. Clinical review by Andrew Esch, MD, MBA.