Veterans Affairs Moves the Needle in Median LOS with Concurrent Care Hospice

When I came to the Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center in Iowa City to direct the Hospice and Palliative Care Program, I looked forward to the challenge of expanding a palliative care team in a large, integrated health care system. Soon after I arrived, I learned from a former Hospice and Palliative Medicine (HPM) fellow about “concurrent care hospice” (concurrent care): the VA would allow patients with incurable disease to receive disease-directed therapy (e.g., immunotherapy, chemotherapy, radiation, IV furosemide), while paying for hospice at the same time. The VA made a conscious decision in 2009 to avoid having veterans make “the terrible choice”, between continuing disease-directed therapy and allowing strong interdisciplinary support from hospice at home.

So Many Questions

Really? How is this being implemented? How do hospices feel about this? I had so many questions! Is this double dipping at the federal government level? How does our team feel about this phenomenon? Who has written the road map? How do we do this in a rural state? What if the veteran gets sick and goes to the emergency room—does the hospice foot the bill?

I realized that I first needed to convince myself, a hospice medical director from the 1990s, that this was a positive and ethical development. Here are the points that seemed important to me:

1. The advent of concurrent care came from the VA Comprehensive End of Life Care Initiative 2009-2012, which responded to the realization that veterans were getting hospice support only 5 percent of the time (2006). This VA initiative:

- Focused on supporting the needs of veterans with serious illnesses and their caregivers

- Removed the requirement that the veteran needs to forgo disease directed therapy in order to receive hospice care, avoiding “the terrible choice” between disease treatment and home-based supportive care

- Showed high variability in the implementation of concurrent care at different VA Medical Centers

2. National data suggests that concurrent care has lower costs, despite simultaneous access to disease treatment and hospice, probably due to less need for crisis emergency department, hospital, and ICU care.

There are some early examples that concurrent care may be starting to take root beyond the VA. For example, concurrent care has occurred in other settings with non-VA payers. Under the Affordable Care Act, children can now receive hospice care while still receiving disease-directed therapies. Private insurers have been known to “carve out” chemotherapy, paying for treatment and hospice at the same time.

3. Concurrent care offers the promise of something better.

Ever since the Medicare Hospice Benefit became permanent in 1986, nothing has budged the short median length of stay in hospice – about twenty-one days. If we are going to have the hospices meet patient needs six months before they die, then hospices need to meet them earlier in their disease trajectory – NOT just when disease-directed therapies are no longer helpful. If the goal is to meet the quality of life and functional support needs of people living with serious illness and their families, then concurrent care might even need to happen soon after diagnosis. Patients and caregivers need a better solution than “the terrible choice”, and I believe we may have found a program that helps with the functional and quality of life decline of serious illness.

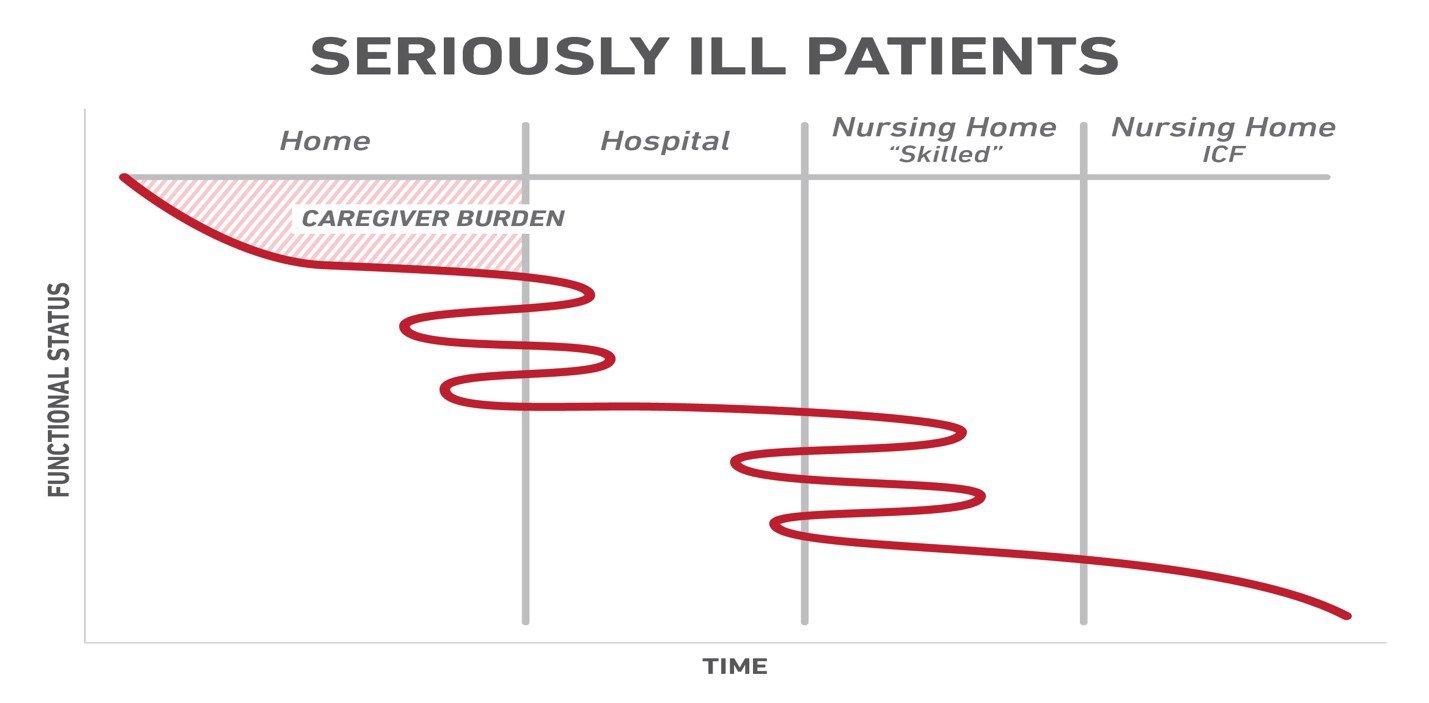

4. Caregivers are shouldering a heavy burden during the functional decline of the veterans. I illustrate what happens with this graphic that I designed to illustrate what happens to veterans at the end of life.

5. Earlier referrals might also stabilize the veteran when he/she is still able to go back home, not wait until they NEED to go to long-term care.

6. The hospices are highly skilled at addressing the social determinants of health — the aloneness or food and housing insecurities. Challenges with cognition and medicine adherence become manifest during home visits.

7. As hospice-appropriate patients are identified and referred, the palliative care team can move upstream through education and direct clinical care to see patients with serious illness closer to the time of diagnosis.

Breaking It All Down

Taking these points together, it seemed that concurrent care was an important service to offer the veterans served by the Iowa City Veterans Administration Medical Center and the associated community-based clinics. With Iowa VA Medical Center leadership support, our team decided to pilot concurrent care systematically for one year.

We asked hospices to meet with us in a biannual call to see what they thought

In Iowa and Illinois (neither are certificate of need states), there are many competing hospices in each county. Last spring and fall, we met with the hospices to whom we refer and ironed out protocols and problematic situations (e.g. the veteran decides to go to the emergency room to deal with a complication of disease-directed therapy). In addition, I stop in and visit hospice colleagues when I am on the road, speaking at outlying VA clinics. Some hospices have been clear that they will not accept concurrent care patients, but they are in the minority. Some hospices have asked if this model is successful, and if it will be adopted by Medicare beyond the VA.

After meeting with the hospices, we met with our very collaborative oncology group, who appeared to be interested in concurrent care for their patients with incurable disease. Initially, we worried that tough conversations about when to stop disease-directed therapy might be postponed. This has not been the case. The option for concurrent care means that we have lost the tug of war that sometimes characterizes palliative-oncology relationships. Both teams share the struggle on the evidence on when to stop immunotherapy, meaning that disease-directed therapies can be continued until very close to death.

Lessons Learned

Working with the hospices and the oncology group, we learned some important lessons. Hospices needed to learn that not all clinical decline was the active dying process, and that reversible conditions such as sepsis or ascending cholangitis might complicate the clinical picture. Sometimes the patients wanted to stop disease-directed therapy before the oncologists thought it was prudent or necessary.

We realized early on that we needed to identify patients in the medical record who are getting hospice support in the community, so we designed concurrent care notes and built a “hospice flag” in the electronic medical record. This helps admitting teams identify, which veterans have concurrent care support. The flag simply states that they should address goals of care, treat as medically appropriate, and call the palliative care team with questions. The palliative care team reinforces that disease-directed treatments are appropriate for patients under concurrent care.

Signs of Success

For all of the learning, adjusting, and growing into concurrent care, we have seen progress first hand. It has been clear that the palliative care and oncology teams have worked hard to make concurrent care work for veterans. In our first year, seventy-eight veterans have had concurrent care out of the total of 397 veterans receiving hospice. Our median length of stay in hospice for the concurrent care patients has increased to forty-five days from an historical median of seventeen days Cancer diagnoses predominated with 83 percent and other chronic disease with 17 percent. One veteran insisted on a death in the ICU.

Most promising is that others are also taking note of the progress and recognizing the value of concurrent care. After a year, the heart failure physician knocked on our door and asked to collaborate. We are currently working out what concurrent care hospice looks like for veterans with advanced heart failure. While the collegial relationships developed with our colleagues has been rewarding, the relationships that we can build with our veterans to provide needed support at an earlier point in the trajectory is what keeps us working on improving and expanding concurrent care.

Same Message, Different Approach

VA Patients

When I present concurrent care hospice to veterans, I do so slowly, with appropriate pauses. This is how I present concurrent care to veterans and their families:

"I would like to talk to you about hospice. Would that be okay?

The VA does hospice differently than the civilian world.

In 2009, the VA realized that veterans were not getting hospice support when they died. And often they were not dying where they wanted to.

For that reason, the VA thinks that we should be offering hospice sooner, when the patient and family might really be able to use the support to be able to stay at home.

The VA calls this concurrent care: you get hospice and all the treatment for your medical illness at the same time.

There is the requirement that you understand that you have an incurable disease.

And two physicians need to agree that you have a prognosis of six months or less—we use guidelines for that decision.

We are wrong about 25 percent of the time, and the patients graduate from hospice.

This happens more often in lung and heart disease. Patients are often sad to see the hospice teams leave…even though that is often good news."

Medical Community

When I talk to residents, hospitalists, and specialty physicians, I use the serious illness chart to explain why we want to talk about hospice early while the veteran is still at home, and might be able to stay at home with the appropriate support interventions. Our palliative care team finds the logistics and level of coordination required for concurrent care patients to be challenging. The specialty teams find it very satisfying to work collaboratively, while caring for their patients with hospice support in the home. Personally, it has been fabulous to work with hospice, specialty, and primary care colleagues to find ways to make hospice work for veterans who have complex and advanced illnesses.

In Conclusion

I often think about how far we have come in terms of recognizing that patients and families need palliative care, long before they are “dying.” Yet, I have a final question. Why hasn’t the VA Concurrent Care model served as a demonstration project for Medicare when CMS was looking for concurrent care demonstration projects? Hospices are currently grappling with the “hospice light” of the Medicare Care Choices Model, which purports to allow concurrent care, but is not really hospice because of markedly lower payments to the hospice programs. Ongoing data collection may add to the compelling story of concurrent care in the VA and its implications for all patients in need of hospice care.

So, if you do not work in a VA, ask your patients if they are veterans. It is possible that the concurrent care model can work for them, even if they are getting disease directed care outside the VA. If you do work in a VA and have experience with concurrent and disease-directed care, we hope to learn from you—we need help from our colleagues in rural and urban settings. Be in touch.