Screening for Delirium: What Clinicians Should Know

Delirium is a significant source of suffering and distress for patients and loved ones. Commonly encountered across treatment settings, it is especially prevalent among patients with serious illness, with studies demonstrating rates of delirium as high as 74% in inpatient palliative care units. The impact of delirium on a patient’s course is often significant. Delirium is associated with increased hospital length of stay, increased rates of admission to a rehab unit or other facility, and an overall rise in morbidity and mortality, not to mention health care costs.

[Delirium] is especially prevalent among patients with serious illness, with studies demonstrating rates of delirium as high as 74% in inpatient palliative care units.

Given these consequences and the accompanying fear, anxiety, and loss of dignity that delirium causes, it is crucial for palliative care clinicians to have a solid understanding of delirium: what it is, how it presents, and how it is evaluated, prevented, and treated.

To start, what is delirium?

Delirium is a neuropsychiatric condition classically characterized by the acute onset of waxing and waning fluctuations in attention and level of arousal. Patients often experience cognitive symptoms (e.g., impaired memory and concentration), perceptual disturbances (e.g., auditory or visual hallucinations), and affective symptoms (e.g., flat or depressed mood, agitation, or euphoria).

Delirium is a neuropsychiatric condition classically characterized by the acute onset of waxing and waning fluctuations in attention and level of arousal.

Delirium is caused by another or multiple medical conditions, and is not the primary diagnosis itself. Multiple potential physiological mechanisms have been proposed including neurotransmitter dysfunction, disruptions in central nervous system network connectivity, neuroinflammation, neuronal aging, and oxidative stress, among others. Despite ongoing research in this area, there is no single accepted pathophysiological pathway or model that satisfyingly explains the development of delirium in all patients. Rather, delirium is often characterized as a final common pathway—the end result of a variety of pathologies that all culminate in the acute disruption of central nervous system functioning.[1]

How does delirium present?

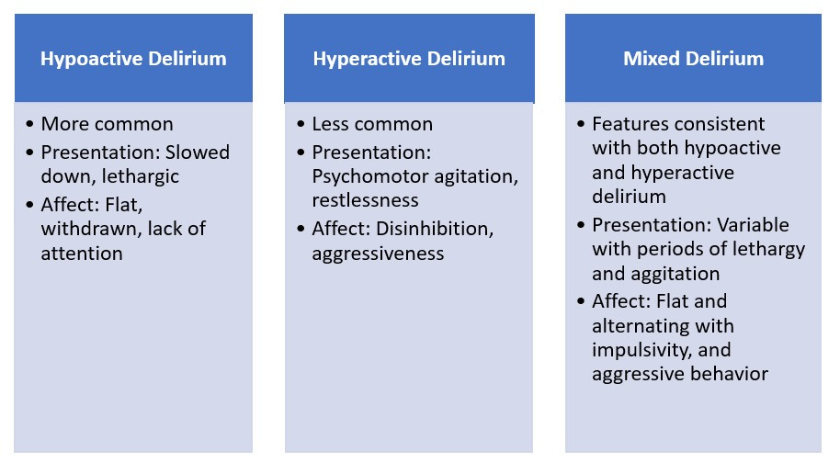

Patients typically initially present with a relatively acute onset of inattentiveness, with cognitive deficits including difficulty recalling information and losing orientation to their surroundings. Frequent accompanying symptoms include affective changes, perceptual disturbances, and disruption in the normal sleep/wake cycle. Based on the specific symptoms a patient presents with, clinicians usually categorize presentations of delirium as either hypoactive or hyperactive. Of note, this distinction is based on the symptoms experienced by the patient, regardless of the underlying cause of the delirium.

Common risk factors and precipitants

While predicting with total certainty which patients will develop delirium during an acute illness is challenging, several known factors increase a patient’s risk. Common risk factors in the general population include advanced age, presence of an underlying neurocognitive disorder (e.g., dementia), history of head injury, certain medical comorbidities (including cardiovascular or renal disease), visual and hearing impairment, and poor nutritional status. Among palliative care patients, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of nine studies identified specific risk factors including older age, hypoxia, dehydration, cachexia, opioid use, anticholinergic burden, and poor Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status. Patients with multiple risk factors are at higher risk of developing delirium, even in the face of what may otherwise be a less acute inciting illness.

Common causes in the general population include medications and toxin effects, metabolic derangements, central nervous system disorders, and infections.

As noted previously, delirium itself is a neuropsychiatric phenomenon precipitated by another acute medical process. Common causes in the general population include medications and toxin effects, metabolic derangements, central nervous system disorders, and infections. In addition to these potential precipitants, patients with cancer are also at risk of developing delirium due to primary and metastatic brain tumors, leptomeningeal disease, paraneoplastic syndromes, certain chemotherapeutic agents, or end-organ failure caused by malignancy.[2]

Additionally, certain cancers may lead to a patient being more likely to experience conditions that cause delirium in the general medical population. For example, patients with certain hematologic malignancies may be in an immunocompromised state, which places them at extremely high risk of developing acute infections, which in turn can precipitate delirium.

How to screen for delirium

Beyond being mindful of the risk factors, clinicians can also implement screening tools to bolster early detection of delirium. Commonly used screening tools include the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM), a CAM variant intended for use in intensive care settings, Confusion Assessment Method-ICU (CAM-ICU), the Nursing Delirium Scale (Nu-DESC), the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS), and the Stanford Proxy Test for Delirium (S-PTD). Scales vary based on the specific cognitive domains they choose to focus on, the overall amount of time needed to complete the screen, and other factors. Other tools are not specific to delirium but can also be used to evaluate cognition, including the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE).

Evaluation

Delirium is diagnosed based on clinical presentation, focusing on the timing of symptom onset, associated symptoms, and thorough mental status and cognitive exams. Providers should assess for cognitive changes, including memory deficits, difficulty sustaining attention, or disorientation. Affective symptoms should also be evaluated including new onset of irritability or mood lability, or, conversely, restricted or flat affect. Perceptual disturbances including visual or auditory hallucinations, illusions, or sensory misperceptions are important to evaluate as well. Hallucinations are a common feature of delirium as are sensory misperceptions, in which patients misinterpret actual stimuli in their environment. For example, a patient might be reporting spiders or other insects on the ceiling of their hospital room. The ceiling may in fact have dark spots or marks on it, which the patient perceives as insects.

The nature of delirium itself makes it difficult for patients to provide a history of recent events, so providers often rely on information provided by family or loved ones.

The nature of delirium itself makes it difficult for patients to provide a history of recent events, so providers often rely on information provided by family or loved ones. Providers can inquire about unusual behaviors, forgetfulness, inattentiveness, recent physical symptoms, or medication changes. Gaining an understanding of the patient’s baseline cognitive functioning is especially helpful given the characteristic rapidity of delirium’s onset.

While delirium itself is diagnosed clinically, arriving at a diagnosis is often the first step, followed by a close exploration of potential triggers. The patient’s individual history will guide history gathering and additional work-up, including which lab studies or diagnostic tests to obtain. In general, a full physical review of systems is warranted. New onset of fevers, rigors, cough, diarrhea, or dysuria might suggest an ongoing infection. A close review of recent medication changes is also crucial. The addition of new deliriogenic medications, such as benzodiazepines, opioids, or anticholinergic agents should be noted. Certain over-the-counter medications may also be problematic including any of the many over-the-counter sleep aides that contain antihistamines (e.g., diphenhydramine, which itself is deliriogenic).

For more information about how medication contributes to delirium, clinicians can play CAPC’s interactive delirium game, A Delirium Whodunit: Understanding the Causes of Delirium.

Continue reading part two of this blog post to learn delirium management strategies and more.

Additional citations

- ↩ Trzepacz. (2000). Is there a final common neural pathway in delirium? Focus on acetylcholine and dopamine. Seminars in Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 5(2), 132–148.

- ↩ Alici, Y., & Breitbart, W. (2021). Delirium. In W. Breitbart, M. Loscalzo, M. Lazenby, W. Lam, Paul Jacobsen, & P. Butow (Eds.), Psycho-Oncology (4th ed.). Oxford University Press, 345-354.

Be the first to read articles from the field (and beyond), access new resources, and register for upcoming events.

SubscribeEdited by Melissa Baron. Clinical review by Andrew Esch, MD, MBA.