Leadership in Palliative Care: Eyes on the Prize

A few years ago, I was trying to do and be everything at once. I was a clinician with a primary care geriatrics practice; an in-patient palliative care consultation attending physician; a researcher on the impact of hospital palliative care; the leader of an academic medical school-based palliative care program; a teacher of fellows, residents and medical students; and Director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care. Just typing all this makes me feel tired. In 2009, the strains and impossibilities of doing all these things led me to take my first sabbatical. I went to Washington, DC, to spend a year as a Health and Aging Policy Fellow, working both on the Senate’s HELP Committee and at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

In addition to appreciation for the deep commitment, expertise and sheer intellect of our so-called “government bureaucrats,” the biggest benefit I got from taking this year away from my job was time to reflect. Time to think about what gave me the greatest sense of accomplishment and joy in my work. Time to realize that trying to do everything was a sure recipe for doing nothing well. Time to realize that what brought me the most satisfaction was trying to solve the puzzle of making the health care system work for my patients, and to realize that—if I disciplined myself to focus on it—I could make a contribution. In other words, time to figure out, among the many things I could be doing with my one life, what is my highest and best use. The result was my decision to work full-time at the Center to Advance Palliative Care and give up all of my other roles and responsibilities. It took me a long time to listen to my inner voice and do what mattered most to me instead of what other people expected me to do—something that I have heard many of my patients say they wished they had done earlier in their lives.

Fascinated by the levers of social transformation and intensely curious about how to influence the incredible complexity and perversity of our health care system, I studied other effective social change efforts. The Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids and ACT UP—two prominent social movements that created a new equilibrium in the U.S.—particularly caught my eye. The former moved us from “there’s nothing we can do about cigarette smoking” to a country with among the lowest smoking rates in the developed world. And ACT UP moved the country from hopelessness and helplessness in the face of an AIDS epidemic killing tens of thousands of people annually to what is now a manageable chronic illness. Each of these initiatives required sustained and multi-sector changes, and each had to overcome powerful and well-resourced political opposition.

How did these profound changes take place? The relatively new field of social entrepreneurship has produced what I have found to be the most informative literature about the how of effective social change. Social entrepreneurs straddle the space between government policy and direct service to solve a problem.

Consider advance care planning as an example—in the past, patients had little to no input over their medical care during serious illness—and where things need to be—routinely asking patients what is most important to them and recommending treatments aligned with their priorities. In 2016, Medicare began reimbursement for advance care planning, in which providers initiate, document and bill for advance care planning conversations. How did this happen? The work required to routinize advance care planning required both social advocacy (such as lobbying Congress and CMS by a number of organizations) and social entrepreneurship (development, testing and refining a solution that can change the status quo and create a new equilibrium). I recommend a recent (short!) book on this framework, titled Getting Beyond Better: How Social Entrepreneurship Works.

The central characteristics of this process include:

- Naming of a stable but inherently unjust equilibrium that causes (in our example of advance care planning) suffering of seriously ill people who lack the means or influence to effect change;

- Development, testing, refining, and scaling of a solution that shifts away from the old equilibrium (doctor knows best) to a new steady state (patients have a right to determine what is done with their own bodies) that fundamentally challenges the old status quo;

- Stabilizing and building a supportive ecosystem (training, law, regulation, payment) around the new equilibrium to sustain and extend its benefit across society

Successful political advocacy in support of advance care planning required evidence of its impact, scalability and acceptability to the public. A series of social entrepreneurs worked for decades to produce that evidence and build the supportive national ecosystem that, finally, enabled the new legislation. These included exemplars like Susan Tolle—who led the development and scaling of POLST—and Bud Hammes—who led the development and scaling of Respecting Choices.

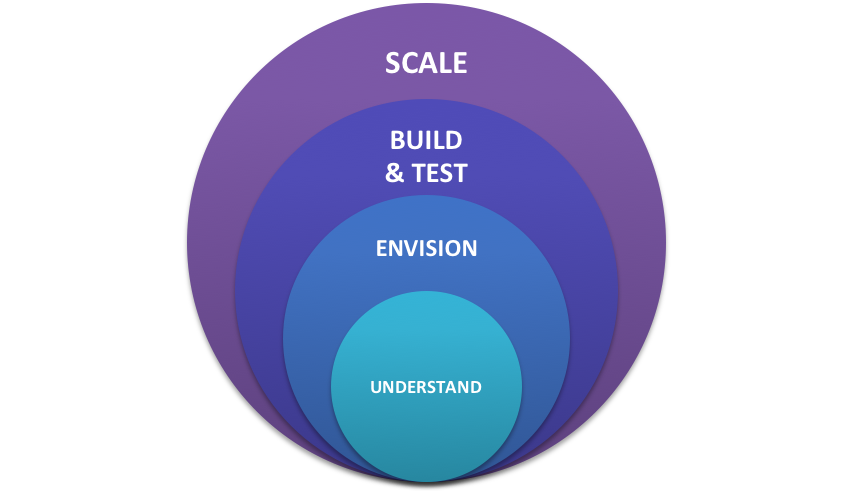

The core principles of social entrepreneurship is a framework involving 4 stages, as graphically depicted above:

- Understand the current equilibrium and what keeps it that way—a process of appreciative inquiry, and listening to key stakeholders, both those invested in the way things have always been done, as well as those who want change;

- Envision what success would look like, in order to strategize backwards from that goal;

- Build, test and modify a model or prototype until it demonstrates the impact sought (“success”) in a measurable, quantifiable and systemic manner; and

- Scaleability of the solution, or the ability to widely replicate it at the lowest possible opportunity cost.

If you read about the history of POLST and Respecting Choices, you will see each of these stages articulated. Application of this framework to scaling advance care planning required:

- Understanding why things are so broken (e.g., lack of training, perverse financial incentives);

- A vision for a new equilibrium (medical care begins with, and is always in orbit around, the priorities and concerns of the patient and the family);

- Building a prototype model, and testing and modifying it (advance care planning via POLST first in Oregon, now across states and care settings, and via Respecting Choices initially in LaCrosse, WI, now with international uptake) along with investment in research, education and training; and

- Scalability via technical assistance, on-line and in-person training, train-the-trainer approaches, coaching, regulatory and accreditation requirements, and changes in payment policy.

On a future post, I will examine the social entrepreneurship framework for the field of palliative care and getting to the prize: palliative care everywhere. Leadership is required from all of us in the field, each of us focused on our own highest and best use—towards the goal of co-creation with patients, families and clinicians to achieve the goal of the right care for the right person at the right time and in the right place, every time.