How to Support AIAN/Native American Populations during COVID-19

This is a continuation of a recent blog post, which explores ways in which COVID-19 has exposed and exacerbated health inequities for Black/African American persons in the United States. In this blog post, we discuss the impact of COVID-19 on American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN)/Native American populations, emphasizing the responsibility of palliative care teams to support this community.

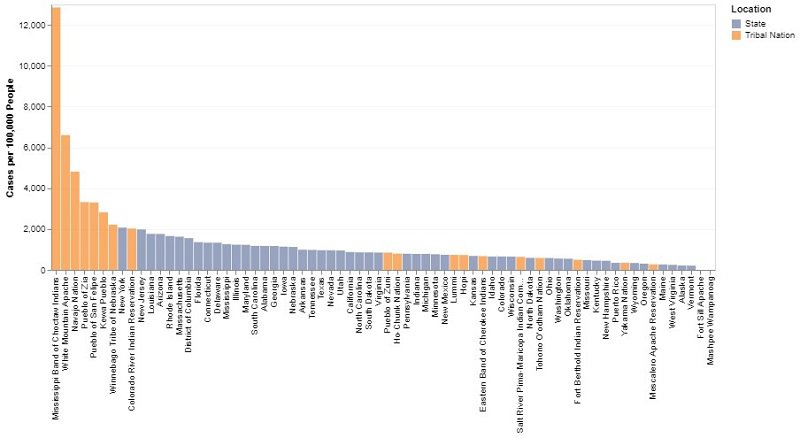

“If Native American tribes were counted as states, the five most [COVID-19] infected states in the country would all be native tribes,” Nicholas Kristof wrote on May 30 for the New York Times. As of July 14, that number has grown to seven tribes. While recent data show that the overall rate of new reported cases has decreased, Native communities continue to be disproportionately impacted by this pandemic, and barriers to care are more pronounced than ever.

“If Native American tribes were counted as states, the five most [COVID-19] infected states in the country would all be native tribes."

Case Rate by Select Tribal Nations and States

As described in an earlier blog post, COVID-19 has exacerbated the historical disparities that have long existed for many racial and ethnic groups – such as Black/African Americans, Hispanics, Latinos, and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN)/Native American populations*. Palliative care teams are uniquely positioned to help establish trust and build meaningful relationships with those who are bearing the disproportionate brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic.

*PLEASE NOTE: There is no universally-accepted convention when discussing AIAN populations. When researching for this blog post, we encountered several terms, including Native Americans, Native populations, First Nations, and Indigenous populations, as well as requests to use specific tribal affiliations whenever possible. After much consideration, we have decided to use the Federal government's term, AIAN, but recognize that it is not without limitations.

As CAPC continues our efforts in this space, we ask that you share the tools and resources that would be most helpful for you, by taking the COVID-19 health disparities survey.

Complete the surveyHealth Care Inequities in AIAN Communities

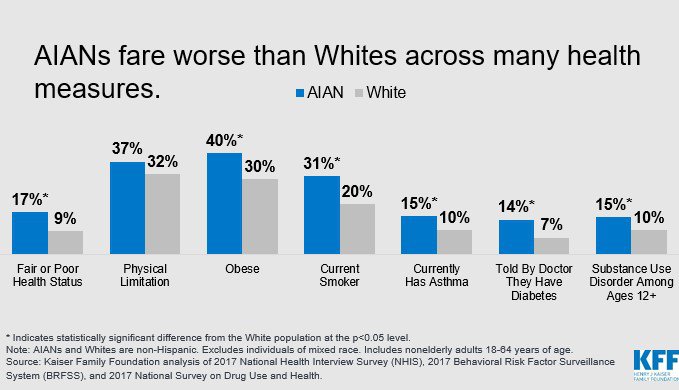

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, health and health care inequities in AIAN populations were well-documented. These include lower life expectancy and disproportionate disease burden, compared to Whites/Caucasians. These inequities are partly attributed to economic adversity, disproportionate poverty, and discrimination in the delivery of health services.

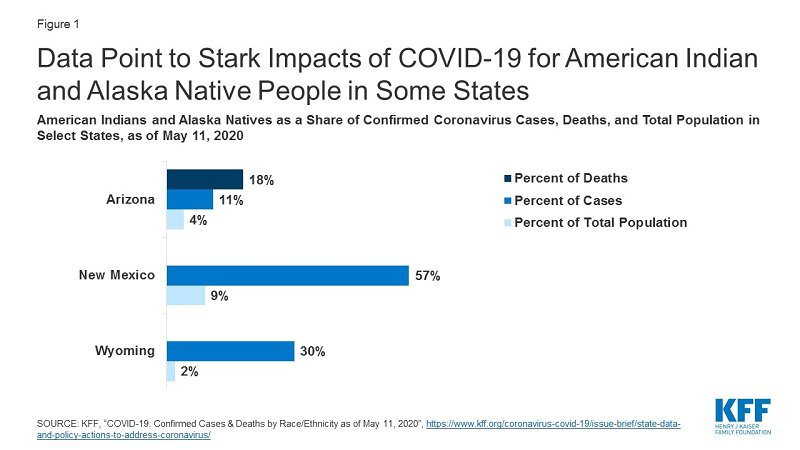

COVID-19 has exacerbated these health injustices, with data showing a distinct negative impact on AIAN communities. For example, in Arizona, AIAN people accounted for 11 percent of coronavirus cases and 18 percent of deaths (as of May 2020), despite only comprising 4 percent of the state’s population. These patterns were similar in New Mexico and Wyoming, and are expected to worsen as COVID-19 hotspots expand in the South and West – see the graph below.

Risk Factors

Similar to other communities disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, there are several factors that increased the risk of COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality among AIAN people, which may inform engagement with the health care system.

1) Increased Exposure

Environmental conditions place some AIAN tribes – particularly those living on reservations or other trust lands – at higher risk of COVID-19 exposure as they are more likely to live in multi-generational housing situations and lack access to clean water and plumbing. These factors increase the risk of COVID-19 infection and chance of spread amongst family members, which is exacerbated by preexisting disparities in chronic conditions that lead to worse outcomes. There have been instances in which entire families have been infected and several members have died. Recognizing the inadequacy of federal and state governmental responses, young Navajo community leaders and organizers have engaged in grassroots efforts to identify needs of families and protect their elders; however, it is hard to measure the impact of this work.

2) Inadequate Access to Services and Testing

With the Indian Health System (IHS) designated as the central mechanism to provide health care services to AIAN people, it is vital to acknowledge that IHS has been historically underfunded. This has led to often substandard health care in AIAN communities. In addition to this, IHS eligibility standards have served to disqualify certain groups within the AIAN community from accessing care. And for those who do qualify, IHS facilities can be hard to access for those who live both on and off reservations – creating further challenges to accessing preventative and tertiary care.

The rapid surge in COVID-19 infections exploited these shortcomings in the AIAN health care infrastructure. Communities experienced significant delays in preventive public health support – particularly in the form of testing supplies – due in large part to structural issues with the IHS, exclusion from certain CDC programs, supply chain issues (similar to those experienced in many rural communities), and slow disbursement of federal monies intended to support COVID-19 response efforts. Beyond that, many local services such as public safety and social supports are funded through casino and tourism revenue, which has been effectively cut-off in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, with telemedicine being promoted as an optimal solution to addressing health care access issues, people on some reservations do not have internet – or even electricity. While recent legislation has focused on reducing barriers to telehealth, much more work is needed to ensure that AIAN populations have the necessary infrastructure to receive equitable care.

3) Lack of Data

It has been very difficult to quantify the extent to which COVID-19 has impacted AIAN communities due to longstanding, systemic failures in data collection. While this is true across populations, it has been particularly egregious for AIANs – both in terms of being accurately reflected in the data, as well as some tribes’ ability to access data for planning purposes. Federal agencies are beginning to make progress on this, but the lag has undoubtedly contributed to misunderstandings about the pandemic’s scope in AIAN communities, and delays in public health measures that could have saved lives.

Where Does Palliative Care Fit In?

As stated in the most recent health care inequity blog post, the National Consensus Project (NCP) Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th Edition includes an expectation that palliative care teams address cultural aspects of care as part of a person-centered intervention. Specifically, teams must:

- Ensure equitable, culturally humble/competent/sensitive care in patient and family interactions;

- Identify opportunities to address the larger forces, structures, and systems that contribute to health and health care inequities

Specialty-trained palliative care clinicians are equipped with skills to reduce health inequities through high-quality, culturally-responsive interactions; yet doing so requires continued practice and attentiveness to both historical and emerging issues across populations.

Specialty-trained palliative care clinicians are equipped with skills to reduce health inequities through high-quality, culturally-responsive interactions[...]

Two key considerations in caring for AIAN patients are the deeply held beliefs and customs that may dictate what care should be provided, and the tremendous variation in those beliefs and customs – both between and within tribes. There are 574 federally-recognized Native tribes, nations, bands, pueblos, communities, and native villages in the U.S., and even more state- and non-governmentally recognized tribes. Furthermore, it is important to remember that only an estimated 22 percent of AIAN populations live on reservations; yet AIAN persons living off tribal lands also bear the legacy of centuries of racist policies and experience stigma and poorer quality care from health care providers. Given this immense variation, ideas about health, illness, and end-of-life care, as well as the role of family and the larger community’s involvement in decision-making, cross the spectrum.

Two key considerations in caring for AIAN patients are the deeply held beliefs and customs that may dictate what care should be provided, and the tremendous variation in those beliefs and customs – both between and within tribes.

The takeaway here is that while learning about specific tribal preferences in advance of the health care interaction can be helpful, clinicians risk doing harm if they deliver care using inaccurate cultural assumptions. (CAPC strongly recommends doing background research; please see selected references at the bottom of this post.) Ultimately, palliative care professionals must remember that each patient has unique preferences and be prepared to modify their approach based on the information provided by the patient and/or family/caregivers. And no matter which beliefs or cultural values a person or family holds, experience of and perceptions about a serious illness are challenging, life-altering, and influenced by both individual and family/community/cultural factors.

The takeaway here is that while learning about specific tribal preferences in advance of the health care interaction can be helpful, clinicians risk doing harm if they deliver care using inaccurate cultural assumptions.

Below we’ve included additional recommendations for providing culturally-sensitive palliative care to AIAN patients.

Avoiding the Victim Narrative

Despite the many historical and current traumas borne by American Indians and Alaska Natives, members of these communities have demonstrated incredible resilience over time. They are doctors, lawyers, artists, business leaders, and – above all – survivors. Too often, well-intended persons or organizations fixate on the negative experiences and consequences that we have described above, inadvertently creating a victim narrative. Therefore, all clinicians should take the time to center themselves in positive imagery and stories that highlight the strength of AIAN people and their communities.

Despite the many historical and current traumas borne by American Indians and Alaska Natives, members of these communities have demonstrated incredible resilience over time.

Before the Interaction

Prior to a meeting with a new AIAN patient and/or family, we recommend the following:

- Partner with colleagues who identify as AIAN and are willing to give recommendations and transparent feedback. Ask for guidance on appropriate phrases or language to avoid when seeing AIAN patients – and then be prepared to redirect if that language is not applicable.

- Mentally reset between seeing patients to help optimize the patient-provider experience. Use a few minutes between visits (e.g., taking a few breaths before walking into the room) to recognize the person’s individuality and follow their lead at the onset of the visit.

- Consider whether or not you have enough time to have a high-quality conversation with the person and their family. For many AIAN persons, information is conveyed through stories, and (like most patients) they are sensitive to being rushed. Avoid interrupting the patient or caregiver as they speak – pauses could be part of communication and allow them to process and reflect back what they understand about their disease and/or care options.

- Consider any implicit biases or unexamined assumptions that you may be carrying. For example, it is widely accepted that certain tribes (e.g., members of the Navajo nation) may be resistant to direct conversations about death and/or advance care planning. However, members of other tribes – and even members within the Navajo nation – might welcome a direct conversation. Furthermore, even among patients who are resistant to these conversations, there may be indirect approaches that can help facilitate discussions to ensure more patient-centered care. Ultimately, as a palliative care professional, you must interrogate your own comfort level with initiating an ACP conversation with the patient and always approach the conversation in a compassionate, caring, kind, and respectful way.

Cultivating and Maintaining Trust

Developing a trusting relationship with AIAN patients and their caregivers can be difficult, given historical injustices perpetrated against them by the medical system and larger society. While there is no perfect path, palliative care professionals can take steps and use certain phrases to overcome these barriers. (Note: the University of New Mexico and the Gallup Indian Medical Center are developing culturally appropriate materials and scripts to navigate discussions with AIAN patients and families; we will share these when they are available.) The following tips have been collected from palliative care providers who work closely with AIAN patients.

- Assess where patients are by asking a question such as, “I am wondering if you can tell me a bit about your health and what has been going on?”

- If the patient/family expresses concern, offer empathy and/or reflection.

- Ask for permission to share what you know. It can be helpful to warn patients about the nature of the discussion and communicate that no harm is intended before disclosing a diagnosis or describing the potential disease trajectory. Remember that it can be sensitive/overwhelming for a patient and their caregivers to discuss a serious illness.

- Explain your purpose (e.g., my goal is to figure out the best care for you and your loved one) and then ask key questions:

- Do you want an interpreter/translator?

- How do you want to receive information?

- How does your family make decisions?

- What will be most helpful to you?

- When requested, facilitate the involvement of traditional healers, if possible. It shows collaboration and willingness to be a true partner in the patient’s care.

- Focus on what is in your sphere of control or influence. If a patient's wishes are misaligned with what is possible at the time, identify how you can support and maintain the relationship in other ways. For example, if a patient must be moved to a different facility (a particularly common occurrence for AIAN patients in New Mexico in the COVID era), have someone from the team regularly update their caregivers to the greatest extent possible.

Developing Appropriate Care Plans

Care plan success for AIAN patients will largely depend on the inclusion of appropriate family members in the planning process, as well as an understanding of personal/cultural priorities and environmental/resource constraints (particularly for those living on reservations).

- Always ask the patient and/or family if others need to be consulted during the decision-making process and during the challenging conversations. For example, in many tribes, the matriarch elder of the family might be the person who must approve of the care plan; in other instances, a patient might want to keep their health information private and not involve other family members or caregivers.

- Listen carefully and use contextual factors to ask the right questions to create an appropriate care plan. One of the consequences of health and health care disparities in AIAN populations is that many are diagnosed with serious illness(es) at much younger ages than the general population. These patients may have different priorities that are not elicited in assessments and care planning tools designed for older patients (e.g., they are more likely to have concerns about who will care for their young children should something happen). Particularly in the COVID era, consider factors such as age, gender, occupation, etc., in ensuring that care plans reflect the priorities of that particular patient.

- Confirm that services required for successful discharge are available, particularly for those living on tribal lands. For instance, if regular follow-up via telehealth is included, make sure that the patient has access to the necessary technology.

- Given the mortality rate associated with COVID-19, palliative care teams will play a role in supporting loved ones in grief and bereavement. Take additional care in learning about the patient/family’s preferences and customs regarding end of life, care of the body, preparation for burial (up to and including appropriate burial practices), and advocate on behalf of the family as needed.

While the previous recommendations have been informed by those who work closely with AIAN populations, please note that much more research is needed to better support evidence-based palliative care practice for these patients.

Conclusion

Palliative care leaders and teams have a critical role in supporting patients who have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. Specialty-trained palliative care professionals can provide respectful, person-centered, culturally-responsive care. When caring for AIAN patients and their families, remember that tribal affiliation may inform preferences and goals – but it is also critical to avoid making assumptions, and to start at the beginning with each individual patient and family. Enable/ask patients to take the lead in the conversations by asking open-ended questions. Discussion of a serious illness with the individual should always be framed by an understanding of what and how the patient wants to know about their illness, informed by respect, compassion, and collaboration to develop an appropriate plan.

Additional Tools and Resources

CAPC Tools and Resources

- CAPC National Seminar Poster: The Northern Arizona Healthcare Navajo Video Project

- CAPC Blog: Be Prepared: Implementing Advance Care Planning Across Cultures

- CAPC Discussion Group: Palliative Care for Underserved/Vulnerable Patients

- CAPC Tool: Equitable Palliative Care Access in COVID-19

- CAPC Master Clinician: Managing Implicit Bias and Its Effect on Health Care Disparities

- CAPC Blogs:

- CAPC On-Demand Webinars:

External COVID-19-Related Health Equity Resources

- Johns Hopkins Center for American Indian Health: COVID-19 Materials Developed for Tribal Use

- NCP Guidelines: Domain 6 (“Cultural Aspects of Care”) and Domain 8 (“Ethical and Legal Aspects of Care”)

- Upcoming NIH Research Call for Proposals: Strategies to Provide Culturally Tailored Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Seriously Ill American Indian and Alaska Native Individuals (R21 Clinical Trial Optional)

- Center for American Progress: Federal policy recommendations to address systemic inequalities that have harmed AIAN populations in COVID-19

- National Congress of American Indians: Tribal Advocacy Materials for Implementing COVID-19 Funding

Selected References

- Gebauer S, Morley SK, Haozous EA, et al. Palliative care for American Indians and Alaska Natives: A review of the literature. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(12):1331-1340.

- Isaacson MJ. Wakanki Ewastepikte: An advance directive education project with American Indian elders. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2017;19(6):580-587.

- Marr L, Neale D, Wolfe V, Kitzes J. Confronting myths: The Native American experience in an academic inpatient palliative care consultation program. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(1):71-76. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0197.

- Isaacson MJ. Addressing palliative and end-of-life care needs with Native American elders. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2018;24(4):160-168. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2018.24.4.160.

- Isaacson MJ, Lynch AR. Culturally relevant palliative and end-of-life care for U.S. Indigenous populations: An integrative review. J Transcult Nurs. 2018;29(2):180-191. doi: 10.1177/1043659617720980.

- Lillie KM, Dirks LG, Curtis JR, Candrian C, Kutner JS, Shaw JL. Culturally adapting an advance care planning communication intervention with American Indian and Alaska Native people in primary care. J Transcult Nurs. 2020; 31(2):178-187. doi: 10.1177/1043659619859055.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the following people who contributed their expertise and reflections to inform the writing of this blog:

- Jeanna Ford, DNP, APRN, ACNS-BC, ACPN, Palliative Care Clinical Nurse Specialist at Presbyterian Healthcare System

- Elizabeth Anderson, LCSW, DSW, Assistant Professor at Western Carolina University

- Lisa Marr, MD, Division Chief of Palliative Medicine at University of New Mexico